Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

Listen To An Excerpt

0:00 /

About The Book

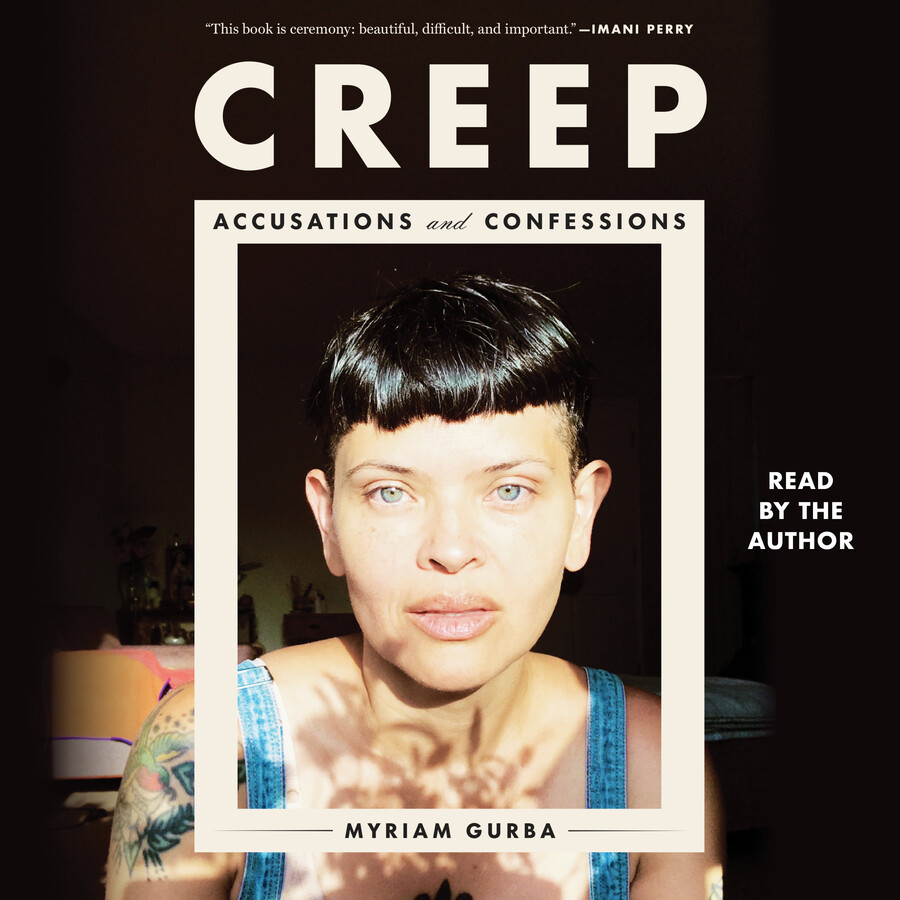

A NATIONAL BOOK CRITICS CIRCLE FINALIST * A LAMBDA LITERARY AWARD WINNER

“Quite simply one of the best books of the decade.” —Los Angeles Review of Books * “The mother of intersectional Latinx identity.” —Cosmopolitan * “Brilliant…a hopeful book…rooted in the steadfast belief other worlds are possible.” —The New York Observer * “Witty, confident, and effortlessly provocative.” —The Philadelphia Inquirer * “The most fearless writer in America.” —Luis Alberto Urrea, Pulitzer Prize finalist and author of Good Night, Irene

A ruthless and razor-sharp essay collection that tackles the pervasive, creeping oppression and toxicity that has wormed its way into society—in our books, schools, and homes, as well as the systems that perpetuate them—from one of our fiercest, foremost explorers of intersectional Latinx identity.

A creep can be a single figure, a villain who makes things go bump in the night. Yet creep is also what the fog does—it lurks into place to do its dirty work, muffling screams, obscuring the truth, and providing cover for those prowling within it.

Creep is “sharp, conversational cultural criticism” (Bustle), a blistering and slyly informal sociology of creeps (the individuals who deceive, exploit, and oppress) and creep culture (the systems, tacit rules, and institutions that feed them and allow them to grow and thrive). In eleven bold, electrifying pieces, Gurba mines her own life and the lives of others—some famous, some infamous, some you’ve never heard of but will likely never forget—to unearth the toxic traditions that have long plagued our culture and enabled the abusers who haunt our books, schools, and homes.

With her ruthless mind, wry humor, and adventurous style, Gurba implicates everyone from William Burroughs to her grandfather, from Joan Didion to her own abusive ex-partner; she takes aim at everything from public school administrations to the mainstream media, from Mexican stereotypes to the carceral state. Weaving her own history and identity throughout, she argues for a new way of conceptualizing oppression, and she does it with her signature blend of bravado and humility.

“Quite simply one of the best books of the decade.” —Los Angeles Review of Books * “The mother of intersectional Latinx identity.” —Cosmopolitan * “Brilliant…a hopeful book…rooted in the steadfast belief other worlds are possible.” —The New York Observer * “Witty, confident, and effortlessly provocative.” —The Philadelphia Inquirer * “The most fearless writer in America.” —Luis Alberto Urrea, Pulitzer Prize finalist and author of Good Night, Irene

A ruthless and razor-sharp essay collection that tackles the pervasive, creeping oppression and toxicity that has wormed its way into society—in our books, schools, and homes, as well as the systems that perpetuate them—from one of our fiercest, foremost explorers of intersectional Latinx identity.

A creep can be a single figure, a villain who makes things go bump in the night. Yet creep is also what the fog does—it lurks into place to do its dirty work, muffling screams, obscuring the truth, and providing cover for those prowling within it.

Creep is “sharp, conversational cultural criticism” (Bustle), a blistering and slyly informal sociology of creeps (the individuals who deceive, exploit, and oppress) and creep culture (the systems, tacit rules, and institutions that feed them and allow them to grow and thrive). In eleven bold, electrifying pieces, Gurba mines her own life and the lives of others—some famous, some infamous, some you’ve never heard of but will likely never forget—to unearth the toxic traditions that have long plagued our culture and enabled the abusers who haunt our books, schools, and homes.

With her ruthless mind, wry humor, and adventurous style, Gurba implicates everyone from William Burroughs to her grandfather, from Joan Didion to her own abusive ex-partner; she takes aim at everything from public school administrations to the mainstream media, from Mexican stereotypes to the carceral state. Weaving her own history and identity throughout, she argues for a new way of conceptualizing oppression, and she does it with her signature blend of bravado and humility.

Reading Group Guide

Get a FREE audiobook by joining our mailing list today! Plus, receive recommendations for your next Book Club read.

By clicking 'Sign me up' I acknowledge that I have read and agree to the privacy policy and terms of use. Free ebook offer available to NEW CA subscribers only. Offer redeemable at Simon & Schuster's ebook fulfillment partner. Must redeem within 90 days. See full terms and conditions and this month's choices.

This reading group guide for Creep includes an introduction, discussion questions, ideas for enhancing your book club, and a Q&A with author Myriam Gurba. The suggested questions are intended to help your reading group find new and interesting angles and topics for your discussion. We hope that these ideas will enrich your conversation and increase your enjoyment of the book.

Introduction

Oppression isn’t an event—it’s an environment. So declares Creep, a radical and unflinching essay collection that indicts the creeps skulking in our neighborhoods and collective consciousness, as well as the systems that allow them to live among us. In eleven essays, Myriam Gurba redefines accountability by analyzing the creeps in our newspaper headlines, politics, and homes, as well as how rhetoric, propaganda, and institutions serve creepy causes. Braiding together stories of literature’s shining stars, rape jokes, and moments both hilarious ad harrowing from her own life, Gurba exposes our societal devotion to toxic traditions and the people who perpetuate them, all in prose that is in turn gleeful, blunt, poetic, and darkly funny.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. Reflect on Gurba’s writing style in Creep—its perspective, rhythm, and tone. What words would you use to describe it? Do you notice any differences across or within pieces?

2. Which is your favorite essay, and why?

3. Think about Gurba’s treatment of William Burroughs, Richard Ramirez, Desiree, Lorena Gallo, and her own experiences with assault and abuse. How does Creep reframe how we typically see true crime narratives depicted? What does Gurba’s approach give readers?

4. How does the California of Creep differ from the California of popular media? Are there any specific lines about California that you felt were especially evocative?

5. The first line of “Mitote” is “Before destroying my idols, I lay flowers at their feet” (page 89). How does this relate to Gurba’s relationship with her grandfather, and Creep’s project overall?

6. How would you describe Gurba’s sense of humor? How does it impact your reading of the book, especially the more difficult topics? Where there any moments of humor that you found especially surprising?

7. We get many glimpses of Gurba’s childhood throughout Creep—from the opening “morbid games” she plays with Renee Jr. in “Tell” (page 1), to her relationship with Desiree in “Locas,” and her experience at Orcutt Junior High School in “Navajazo” (page 158). How do these anecdotes demonstrate and shape Gurba’s worldview? Can you identify similar moments of realization or indignation in your own life?

8. Think about the major relationships Gurba dramatizes in Creep—for example, with Desiree, her Abeulito, and her girlfriend Sam. Which did you find the most emotionally or narratively compelling? Why do you think that is?

9. In the titular essay, Gurba reflects on the murder of her sister’s fifteen-year-old friend by her seventeen-year-old ex-boyfriend. “Without rage, how do people heal? Without rage, how does one produce dignity?” Gurba wonders (page 273). What role does anger have in Gurba’s conception of a better world? What other instances of generative anger are there in Creep?

10. “Creep” is the collection’s longest essay. What emotions did it bring up for you? Why do you think Gurba chose to conclude with this essay?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. Choose a few events that Creep explores—for example, the San Gabriel Valley Tribune article that reports Desiree’s involvement in gift card fraud (page 5), or Ingrid Escamilla Vargas’ murder (page 175)—and write a new newspaper headline in the spirit of reconfiguring dominant narratives.

2. In “The White Onion,” Gurba writes, “These days, I find what Didion doesn’t show more interesting than what she tells. Literary criticism, along with history, hands me a scalpel, enabling me to slice open the stomachs of those subjects made visible by her prose” (page 152). Select a Joan Didion work that appears in Creep—Run, River; “Guaymas, Sonora,” “The White Album,” or Where I Was From—and read it for your next book club. In your discussion, analyze Didion’s silences, and compare and contrast her California with that of Gurba’s in Creep.

3. Select one piece from Creep and read it closely together—research the references Gurba makes, pay close attention to the rhetorical devices she employs, and discuss how the essay connects and what it contributes to the collection as a whole.

A Conversation with Myriam Gurba

What did you bring from your experience writing Mean to your experience writing Creep? On a craft and research level, how were the processes similar and different?

Creep is an unorthodox sequel to my true crime memoir Mean. While Mean chronicles my experience of surviving stranger-perpetrated sexual assault, Creep closely examines the impact of intimate partner violence. Typically, a sequel follows the same form and genre as its predecessor, but I deviated from both of those when I set out to write Creep. Instead, I used the personal essay, in combination with history and cultural criticism, to continue the literary and political project initiated by Mean. Specifically, I wanted to introduce readers to the dangerous conditions under which I wrote Mean.

Stylistically, Mean and Creep share key similarities. For instance, the texture of Mean was created through collaging. I collected personal ephemera and inserted it into the narrative so that readers could experience contemporary artifacts that might create an illusion of intimacy, of the audience being granted access into my private world. Some examples of ephemera from Mean include my university class schedules, excerpts of essays I wrote while completing my bachelor’s degree, and some poetry written by my attacker. Collaging also happens in Creep. Rather than narrate the physical injuries my abuser inflicted on me, I insert medicals records into the text. These records function as literary x-rays, allowing the reader to see past the charade of normalcy in which I had to participate for self-preservation. These medical records inventory the physical harm which I sustained but was prohibited from discussing by my abuser.

I enjoy doing research and learned from missteps I made while writing Mean. I tried not to reproduce those mistakes when writing Creep. One of the lessons I learned from Mean is that when researching femicide, I must protect myself from the effects of vicarious trauma. I worked hard to insulate myself from such injury while working on Creep. One method that I used was to limit the amount of time I spent with certain materials. Once my gut would tell me that more time spent with research materials was going to be harmful, I stepped away from the work and engaged in a restorative activity. Baking was one of these restorative activities and while writing Creep, I baked my ass off. I have mastered the apple pie, and my scones are exquisite.

What does the epigraph mean to you? Why did you choose it?

The epigraph is a nod to The Plain in Flames, a short story collection published by Mexican author Juan Rulfo, my grandfather’s frenemy. I chose the lines because I appreciate their moral ambiguity.

How did you decide on the order of the essays?

I very deliberately placed the collection’s title essay at the end of the book. The graphic violence described by “Creep” challenges readers, and had it led the collection, some readers might have had an even harder time stomaching it. Cumulatively, the essays create a fog of sorts, one through which I, the narrator, lead the reader. Once the audience arrives at “Creep,” they are immersed in my world and will likely have a harder time turning away from the violence that they encounter on the page.

Methodologically speaking, how does queerness function in Creep?

Creep appropriates stylistic and structural tics found in Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo, a gothic novel set in a fictional Mexican ghost town and narrated by the dead. Some critics have accused Rulfo’s fractal masterpiece of having no core and I love that! Creep also lacks a core and I believe that that is the core of the book’s queerness. Creep has no singular thesis. Instead, its core is dynamic. It shape-shifts, adapts, appropriates, rebels, and is reborn as needed.

Was there a particular moment or scene that was especially pleasurable to write? Is there a line, section, or chapter of which you’re especially proud?

I really enjoyed writing this line in the acknowledgments section, “And to everyone who got in the way of this book happening, fuck you.”

What is the relationship between humor and heaviness in Creep (and in life)?

In order to live, Joan Didion told stories. In order to live, I tell jokes. Humor protects me from pain both on and off the page and I encourage survivors of gender-based violence to use humor in their recovery. Laughing at rapists and turning them into the butt of jokes is a quick and effective way of restoring one’s dignity. I meditate on the distinctions between survivor-generated humor versus perpetrator-generated humor in the essay “Slimed.” I’m particularly fascinated by the notion of rape as a misogynist practical joke.

What does it feel like to write about your childhood? Your ancestors?

I enjoy writing about my childhood. I had A LOT of fun as a kid. I also had outrageously high self-esteem despite a decade of terrible haircuts. I feel compelled to write as much as I possibly can about my ancestors because doing so is part of my spiritual practice. I engage in ancestor veneration, but I don’t approach the practice as idealization. At times, ancestor veneration veers into the sphere of reckoning. I am especially interested in correcting absences. My family descends from various populations, including nations indigenous to what is now called Mexico. We also descend from enslaved Africans trafficked in the Americas. My practice of ancestor veneration spurs me to research, reconstruct, and write our histories as a form of spiritual resistance, an antidote to the amnesia imposed by settler colonialism. “Mitote,” an essay that functions as an anti-tribute to my maternal grandfather, was written in this vein. I love my grandfather, but he could also be a real asshole.

Near the very end of the book, you write “A book and a life are works of art. Making art isn’t inherently cathartic. Instead, it can be a protective cocoon.” How does this relate to your experience developing and writing Creep?

When Mean published, I was asked the same stale question over and over again. Was the experience of writing about sexual assault “cathartic?” The question made me want punch the people asking it in the mouth. When I was working on Mean, I didn’t give a fuck about catharsis; I was trying to stay alive. I was living with a man whom I feared might kill me. One of the few places where I could hide from my abuser was my imagination. My art was another place. While writing Mean was protective, it was never purgative. Perhaps writing about trauma is cathartic for some but there are many of us who seek healing using other modalities. Also, catharsis is supposed to be the reader’s reward, not the artist’s. Aristotle taught that catharsis is aroused in the audience of those watching a tragedy. It does not belong to the author of the tragedy. I wish that the myth of artmaking as catharsis would die.

What do you hope readers take away from reading Creep?

The desire to buy everything I ever have or will write. Just kidding! Honestly, I hope that readers experience some entertainment or amusement. I do write to entertain. I can’t help it. I also hope that those who want or need edification experience it. My greatest hope is that readers are spurred to participate in social movements that combat the forms of violence condemned by the book. Awareness is useless without action.

Introduction

Oppression isn’t an event—it’s an environment. So declares Creep, a radical and unflinching essay collection that indicts the creeps skulking in our neighborhoods and collective consciousness, as well as the systems that allow them to live among us. In eleven essays, Myriam Gurba redefines accountability by analyzing the creeps in our newspaper headlines, politics, and homes, as well as how rhetoric, propaganda, and institutions serve creepy causes. Braiding together stories of literature’s shining stars, rape jokes, and moments both hilarious ad harrowing from her own life, Gurba exposes our societal devotion to toxic traditions and the people who perpetuate them, all in prose that is in turn gleeful, blunt, poetic, and darkly funny.

Topics & Questions for Discussion

1. Reflect on Gurba’s writing style in Creep—its perspective, rhythm, and tone. What words would you use to describe it? Do you notice any differences across or within pieces?

2. Which is your favorite essay, and why?

3. Think about Gurba’s treatment of William Burroughs, Richard Ramirez, Desiree, Lorena Gallo, and her own experiences with assault and abuse. How does Creep reframe how we typically see true crime narratives depicted? What does Gurba’s approach give readers?

4. How does the California of Creep differ from the California of popular media? Are there any specific lines about California that you felt were especially evocative?

5. The first line of “Mitote” is “Before destroying my idols, I lay flowers at their feet” (page 89). How does this relate to Gurba’s relationship with her grandfather, and Creep’s project overall?

6. How would you describe Gurba’s sense of humor? How does it impact your reading of the book, especially the more difficult topics? Where there any moments of humor that you found especially surprising?

7. We get many glimpses of Gurba’s childhood throughout Creep—from the opening “morbid games” she plays with Renee Jr. in “Tell” (page 1), to her relationship with Desiree in “Locas,” and her experience at Orcutt Junior High School in “Navajazo” (page 158). How do these anecdotes demonstrate and shape Gurba’s worldview? Can you identify similar moments of realization or indignation in your own life?

8. Think about the major relationships Gurba dramatizes in Creep—for example, with Desiree, her Abeulito, and her girlfriend Sam. Which did you find the most emotionally or narratively compelling? Why do you think that is?

9. In the titular essay, Gurba reflects on the murder of her sister’s fifteen-year-old friend by her seventeen-year-old ex-boyfriend. “Without rage, how do people heal? Without rage, how does one produce dignity?” Gurba wonders (page 273). What role does anger have in Gurba’s conception of a better world? What other instances of generative anger are there in Creep?

10. “Creep” is the collection’s longest essay. What emotions did it bring up for you? Why do you think Gurba chose to conclude with this essay?

Enhance Your Book Club

1. Choose a few events that Creep explores—for example, the San Gabriel Valley Tribune article that reports Desiree’s involvement in gift card fraud (page 5), or Ingrid Escamilla Vargas’ murder (page 175)—and write a new newspaper headline in the spirit of reconfiguring dominant narratives.

2. In “The White Onion,” Gurba writes, “These days, I find what Didion doesn’t show more interesting than what she tells. Literary criticism, along with history, hands me a scalpel, enabling me to slice open the stomachs of those subjects made visible by her prose” (page 152). Select a Joan Didion work that appears in Creep—Run, River; “Guaymas, Sonora,” “The White Album,” or Where I Was From—and read it for your next book club. In your discussion, analyze Didion’s silences, and compare and contrast her California with that of Gurba’s in Creep.

3. Select one piece from Creep and read it closely together—research the references Gurba makes, pay close attention to the rhetorical devices she employs, and discuss how the essay connects and what it contributes to the collection as a whole.

A Conversation with Myriam Gurba

What did you bring from your experience writing Mean to your experience writing Creep? On a craft and research level, how were the processes similar and different?

Creep is an unorthodox sequel to my true crime memoir Mean. While Mean chronicles my experience of surviving stranger-perpetrated sexual assault, Creep closely examines the impact of intimate partner violence. Typically, a sequel follows the same form and genre as its predecessor, but I deviated from both of those when I set out to write Creep. Instead, I used the personal essay, in combination with history and cultural criticism, to continue the literary and political project initiated by Mean. Specifically, I wanted to introduce readers to the dangerous conditions under which I wrote Mean.

Stylistically, Mean and Creep share key similarities. For instance, the texture of Mean was created through collaging. I collected personal ephemera and inserted it into the narrative so that readers could experience contemporary artifacts that might create an illusion of intimacy, of the audience being granted access into my private world. Some examples of ephemera from Mean include my university class schedules, excerpts of essays I wrote while completing my bachelor’s degree, and some poetry written by my attacker. Collaging also happens in Creep. Rather than narrate the physical injuries my abuser inflicted on me, I insert medicals records into the text. These records function as literary x-rays, allowing the reader to see past the charade of normalcy in which I had to participate for self-preservation. These medical records inventory the physical harm which I sustained but was prohibited from discussing by my abuser.

I enjoy doing research and learned from missteps I made while writing Mean. I tried not to reproduce those mistakes when writing Creep. One of the lessons I learned from Mean is that when researching femicide, I must protect myself from the effects of vicarious trauma. I worked hard to insulate myself from such injury while working on Creep. One method that I used was to limit the amount of time I spent with certain materials. Once my gut would tell me that more time spent with research materials was going to be harmful, I stepped away from the work and engaged in a restorative activity. Baking was one of these restorative activities and while writing Creep, I baked my ass off. I have mastered the apple pie, and my scones are exquisite.

What does the epigraph mean to you? Why did you choose it?

The epigraph is a nod to The Plain in Flames, a short story collection published by Mexican author Juan Rulfo, my grandfather’s frenemy. I chose the lines because I appreciate their moral ambiguity.

How did you decide on the order of the essays?

I very deliberately placed the collection’s title essay at the end of the book. The graphic violence described by “Creep” challenges readers, and had it led the collection, some readers might have had an even harder time stomaching it. Cumulatively, the essays create a fog of sorts, one through which I, the narrator, lead the reader. Once the audience arrives at “Creep,” they are immersed in my world and will likely have a harder time turning away from the violence that they encounter on the page.

Methodologically speaking, how does queerness function in Creep?

Creep appropriates stylistic and structural tics found in Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo, a gothic novel set in a fictional Mexican ghost town and narrated by the dead. Some critics have accused Rulfo’s fractal masterpiece of having no core and I love that! Creep also lacks a core and I believe that that is the core of the book’s queerness. Creep has no singular thesis. Instead, its core is dynamic. It shape-shifts, adapts, appropriates, rebels, and is reborn as needed.

Was there a particular moment or scene that was especially pleasurable to write? Is there a line, section, or chapter of which you’re especially proud?

I really enjoyed writing this line in the acknowledgments section, “And to everyone who got in the way of this book happening, fuck you.”

What is the relationship between humor and heaviness in Creep (and in life)?

In order to live, Joan Didion told stories. In order to live, I tell jokes. Humor protects me from pain both on and off the page and I encourage survivors of gender-based violence to use humor in their recovery. Laughing at rapists and turning them into the butt of jokes is a quick and effective way of restoring one’s dignity. I meditate on the distinctions between survivor-generated humor versus perpetrator-generated humor in the essay “Slimed.” I’m particularly fascinated by the notion of rape as a misogynist practical joke.

What does it feel like to write about your childhood? Your ancestors?

I enjoy writing about my childhood. I had A LOT of fun as a kid. I also had outrageously high self-esteem despite a decade of terrible haircuts. I feel compelled to write as much as I possibly can about my ancestors because doing so is part of my spiritual practice. I engage in ancestor veneration, but I don’t approach the practice as idealization. At times, ancestor veneration veers into the sphere of reckoning. I am especially interested in correcting absences. My family descends from various populations, including nations indigenous to what is now called Mexico. We also descend from enslaved Africans trafficked in the Americas. My practice of ancestor veneration spurs me to research, reconstruct, and write our histories as a form of spiritual resistance, an antidote to the amnesia imposed by settler colonialism. “Mitote,” an essay that functions as an anti-tribute to my maternal grandfather, was written in this vein. I love my grandfather, but he could also be a real asshole.

Near the very end of the book, you write “A book and a life are works of art. Making art isn’t inherently cathartic. Instead, it can be a protective cocoon.” How does this relate to your experience developing and writing Creep?

When Mean published, I was asked the same stale question over and over again. Was the experience of writing about sexual assault “cathartic?” The question made me want punch the people asking it in the mouth. When I was working on Mean, I didn’t give a fuck about catharsis; I was trying to stay alive. I was living with a man whom I feared might kill me. One of the few places where I could hide from my abuser was my imagination. My art was another place. While writing Mean was protective, it was never purgative. Perhaps writing about trauma is cathartic for some but there are many of us who seek healing using other modalities. Also, catharsis is supposed to be the reader’s reward, not the artist’s. Aristotle taught that catharsis is aroused in the audience of those watching a tragedy. It does not belong to the author of the tragedy. I wish that the myth of artmaking as catharsis would die.

What do you hope readers take away from reading Creep?

The desire to buy everything I ever have or will write. Just kidding! Honestly, I hope that readers experience some entertainment or amusement. I do write to entertain. I can’t help it. I also hope that those who want or need edification experience it. My greatest hope is that readers are spurred to participate in social movements that combat the forms of violence condemned by the book. Awareness is useless without action.

About The Reader

Myriam Gurba is a writer and artist. She is the author of the true crime memoir Mean, which was a New York Times Editors’ Choice, a Lambda Literary award finalist, and was named one of the “Best LGBTQ Books of All Time” by O, the Oprah Magazine. Her essays have appeared in The Paris Review, Time, Los Angeles Times, and in other publications. She lives in Pasadena, California.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster Audio (September 5, 2023)

- Runtime: 11 hours and 11 minutes

- ISBN13: 9781797165738

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Creep Unabridged Audio Download 9781797165738

- Author Photo (jpg): Myriam Gurba © Geoff Cordner(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit