Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

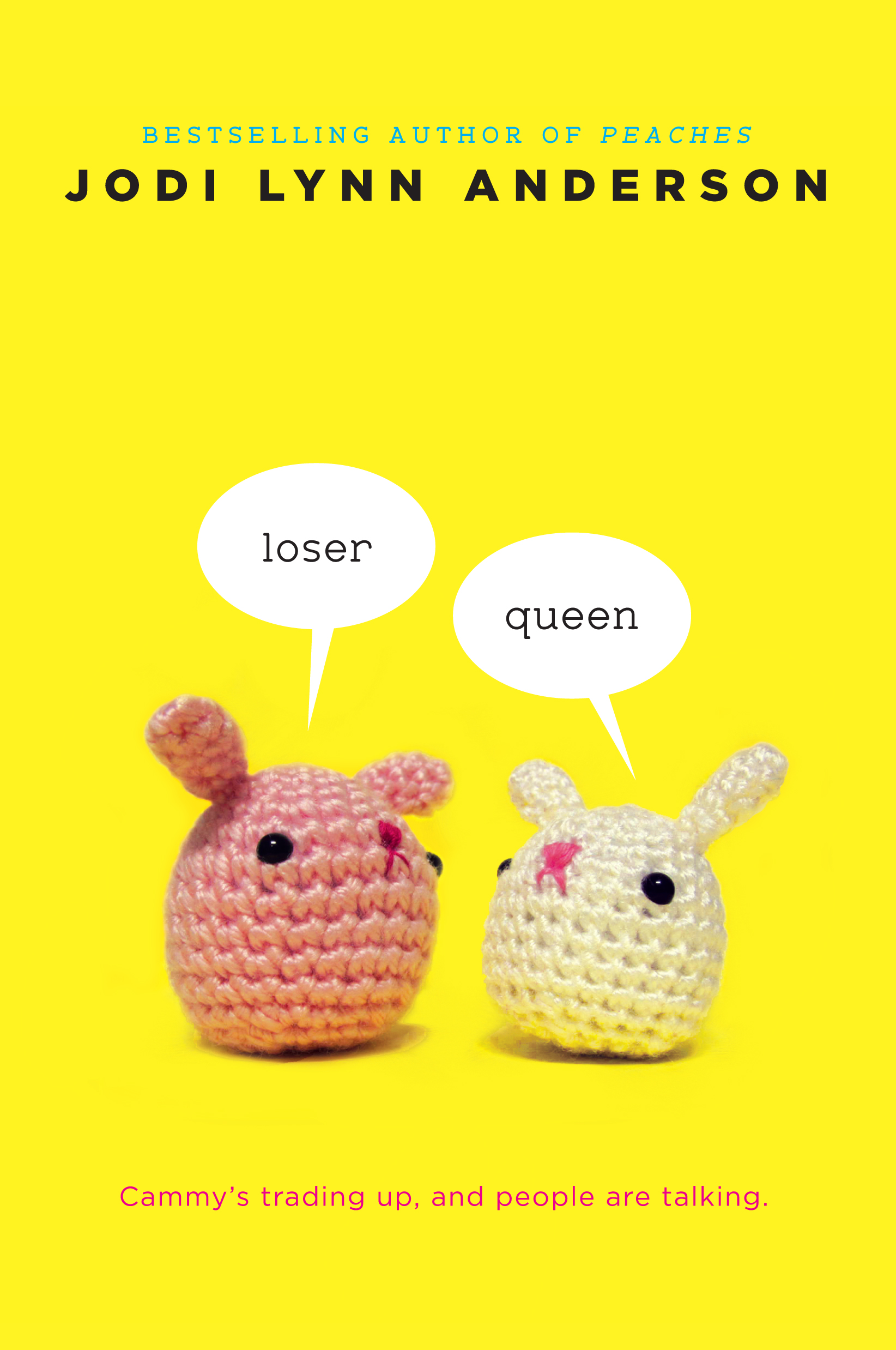

Cammy Hall is what anyone would describe as a loser. She lives with her grandparents and has adopted their way of life… right down to the comfortable shoes and early bedtime. And can she help it that she actually likes to knit?

At school, her skills with knitting needles and some yarn go completely unappreciated: people like Bekka Bell reign while Cammy and her best friend, the fearless Danish exchange student Gerdi, watch from the sidelines. Cammy’s used to being an outsider; after years of humiliating moments, her goal is simply to fly under the radar. Then she suddenly starts receiving mysterious text messages that lead her right to all the embarrassing secrets about the most popular kids in school. Cammy never expected to be able to climb up the high school food chain, and the agenda of the texter may be questionable—but how can she possibly give up the chance to be Queen?

This is the print version of the groundbreaking online interactive serial LOSER/QUEEN that premiered in July 2010 on www.loserqueen.com. Each week, readers voted on major plot twists. The winning choice was then encorporated into the next week's chapters. Now that voting—and the book—are complete, LOSER/QUEEN will be published as a paperback and packed with extras from the author… and readers will have the opportunity to own the book they helped create!

Jodi Lynn Anderson, the national bestselling author of Peaches and The Secrets of Peaches, has lived in Georgia, Costa Rica, and New York, but she currently lives in Washington, D.C.

Brittney Lee is a designer and animator. She lives in Emeryville, CA.

At school, her skills with knitting needles and some yarn go completely unappreciated: people like Bekka Bell reign while Cammy and her best friend, the fearless Danish exchange student Gerdi, watch from the sidelines. Cammy’s used to being an outsider; after years of humiliating moments, her goal is simply to fly under the radar. Then she suddenly starts receiving mysterious text messages that lead her right to all the embarrassing secrets about the most popular kids in school. Cammy never expected to be able to climb up the high school food chain, and the agenda of the texter may be questionable—but how can she possibly give up the chance to be Queen?

This is the print version of the groundbreaking online interactive serial LOSER/QUEEN that premiered in July 2010 on www.loserqueen.com. Each week, readers voted on major plot twists. The winning choice was then encorporated into the next week's chapters. Now that voting—and the book—are complete, LOSER/QUEEN will be published as a paperback and packed with extras from the author… and readers will have the opportunity to own the book they helped create!

Jodi Lynn Anderson, the national bestselling author of Peaches and The Secrets of Peaches, has lived in Georgia, Costa Rica, and New York, but she currently lives in Washington, D.C.

Brittney Lee is a designer and animator. She lives in Emeryville, CA.

Excerpt

LOSER/QUEEN CHAPTER 1

AT 8:45 ON MONDAY MORNING, MRS. WHITE WAS TRYING TO get a handle on her homeroom students. The students’ voices rose loudly above the blaring sound of Channel One, a news show that was broadcasted throughout the school each morning. On-screen, shots of the newscaster were interspersed with commercials about “high school needs,” like dandruff shampoo and matte foundation. Cammy Hall always wondered how they justified subjecting fifteen-year-old girls to watching maxi-pad absorption demos in a room full of fifteen-year-old guys.

Martin Littman sat two seats to Cammy’s right, snickering at the ads, and then grinning at her. He had long curly hair, wet lips, and high cheekbones. He was a complete buffoon, and inexplicably, extremely popular. “Prune juice,” he mouthed at Cammy, because on the first day back to school—two weeks ago—Cammy’s grandma had packed prune juice with her lunch, and Martin—as sharp-eyed as he was dim-witted—had managed to remember this little fact. That’s when Cammy and her best friend, Gerdi, had agreed to resume eating their lunches out behind the school by the Dumpsters, like they had just about every day the previous year.

She glanced over at Gerdi sitting across the room. Gerdi pulled a shiny tube top out of her backpack and waved it at her. She’d shown Cammy the top on their ride into school this morning, and now Gerdi was baiting her with it.

What’s it for? Cammy had asked, trying not to notice how fast Gerdi was driving. Ignoring Gerdi’s carelessness was something she tried to do every time they were in the car, in order to keep her sanity.

Homecoming.

Cammy had sighed pointedly. Gerdi had sighed back in response. It’s not an execution, Cammy, it’s a dance. Gerdi, who was from Denmark, pronounced “dance,” “dunce.” Now she was making the tube top dunce above her bag, smiling at Cammy encouragingly.

Cammy grinned, thinking of how Gerdi always acted so much less sophisticated than she looked. Today she was dressed in a purple, off-the-shoulder T-shirt and a pair of black jeans, with tiny black leather boots her father had sent her from Denmark. Her short brown bob was not pretty, per se, but it was European and striking and only made more of Gerdi’s perfect, wide cheekbones and full, rosy Danish cheeks. She looked like a cross between the little Dutch Boy from those paint cans and the lead singer of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs. Gerdi always looked very cool, even when she was making clothes dance. But Cammy knew better—Gerdi slept with a stuffed platypus, and had recently made a scrapbook called Gerdi’s Book of Hot Guys, like a third grader.

Finally, Gerdi stuffed the top into her backpack, gleeful, obviously excited about the dunce. But then again, for lots of reasons, things were easier for Gerdi.

In front of Cammy, Bekka Bell and her friend Maggie Flay were passing notes back and forth. Cammy glimpsed her name interspersed in the note Bekka opened onto her desk. Well, not her real name. Her nickname. The one she’d been christened with in fifth grade, when she’d gotten the flu and puked up her ham sandwich in the middle of the cafeteria: Hammy.

Gerdi wasn’t nicknamed after pork. That was one reason it was easier for her. For another thing, Gerdi was an outcast only by chance. She was pretty, smart, fun-loving, savvy. Her one mistake was that she had appeared at Browndale during seventh grade, in the middle of the school year, as an exchange student, toting a backpack with a cartoon character on the back, a thick Danish accent, and an arsenal of soon-to be-butchered English phrases. She’d been immediately shunned.

Cammy, on the other hand, was a born outsider. She’d cemented her position at the bottom of the Browndale High School food chain over many years of careful self-humiliation. Wearing a tube top to the homecoming dance was not on the list of humiliations she wanted to explore further. She hadn’t said it to Gerdi, but she’d be willing to bet a hundred dollars that someone would call her a sausage by the end of the night.

It wasn’t just her pudginess. There was her awkwardness with people she didn’t know that well. Also, there was the time she’d gotten her head stuck in between the bars of the gates while peering at the prairie dogs on a trip to the zoo, and the time she had tried to dress up as a sexy Spanish dancer for an eighth grade Halloween party, and everyone had thought she was supposed to be Norman’s mother from Psycho. There was her tendency to drool. And the fact that her eyebrows were eerily identical to Frieda Kahlo’s.

Cammy pulled out her knitting needles and yarn from under her desk, and tried to concentrate on them. Knitting was a skill her grandmother had taught her to make herself feel calm and peaceful. Today, she was working on a small amigurumi pigeon.

In front of her, Bekka ran her hands through her hair endlessly, plucking off the split ends, caressing the strands and working through the tangles, holding her long red hair as if it were gold. Bekka’s hair, which had grown miraculously silky and manelike between seventh and eighth grade, was her pride and joy. Occasionally, she would flick it back completely and it would fly into Cammy’s face or land softly on her desk with a gentle patter. The constant self-worshipping hair stroking always drove Gerdi bananas. From across the room, she was predictably throwing mournful, annoyed looks at Cammy, urging her, with her hands, to pull Bekka’s hair.

But Cammy channeled all of her anger into her tiny pigeon instead. She reflected on her new school year’s resolution. Junior high and even freshman year had been a long string of embarrassing events. But she was determined: This would be her year of living it down. Or, at least, of being completely invisible.

Up front, a Clearasil ad came on. The class watched as an impossibly beautiful girl on-screen agonized over whether the hottie waiting for the bus would see her zit or not. Gerdi was rolling her eyes and sinking back into her chair, pretending to die of American commercialism. Bekka and Maggie were whispering that the nose of the girl on TV was too big. Cammy tried to tune them out, leaned back slightly in her seat, casually turning her head to peer over her shoulder. Luke Bryant was sitting two seats diagonally behind her.

Cammy leaned back a little more. She let her eyes drift to him—first his hands, holding a pencil and twirling it around and around. Then up to his face. He had dreamy hazel eyes and big hands, and he looked like a drummer or something, with finely muscled arms and dark shaggy hair. His expression was inscrutable, his eyes on the ceiling, his mind clearly somewhere else. He laid the pencil down and picked at the spiral of his notebook.

In fifth grade Cammy had transferred her girlhood interest in unicorns to an interest in Luke. Coincidentally, he was like a unicorn in a couple of key ways: He was beautiful and he was completely inaccessible.

Of course everyone is in love with him, Gerdi had said. Love for aloof, inaccessible men was written into the female DNA. Just look at Mr. Darcy from Pride and Prejudice. Or that mean, old blind guy in Jane Eyre. On Monday one of the freshmen had actually cried after Luke had said hi to her in the hallway. The only thing that kept girls from throwing their underwear at Luke onstage was that he wasn’t in any of the plays.

Cammy drifted off, thinking about the old blind guy in Jane Eyre. She couldn’t remember: How had he lost his eyes? Had they been pecked out by a bird or something? Still, he had always sounded miraculously hot, even without eye—

Suddenly she realized Luke’s eyes weren’t on the ceiling, but on the pigeon in her lap. With a quizzical expression, he glanced up and met her eyes, and gave her the slightest hint of a smile. She snapped her head back around, shooting forward so that a tiny piece of spit flew out of her mouth and landed on the back of Bekka’s collar. Mortified, Cammy tried to pull herself together. She didn’t dare look back at Luke to find out if he’d seen. She gazed at the drop of spit sitting on Bekka’s collar, debating on whether or not she’d try to wipe it off.

Up front, Mrs. White was pulling up at her tan stockings for the tenth time. She then started to move up and down the aisles, patting Cammy’s shoulder as she passed her. Cammy shrank under her touch; being one of Mrs. White’s favorites always felt like being a harbinger of doom.

It’s like being in the club of lonely ladies who wear bad outfits and are sad about men, Gerdi had said recently. The scary thing was, Cammy already had the outfits.

Outside, it had just started to drizzle. A stirring drew Cammy’s eyes to the window. There was a movement in the grass. An injured rabbit was flopping away from the road.

Cammy was frozen. She sat and agonized, wondering what to do about the rabbit. She hoped he would just die quickly. But clearly, the rabbit wasn’t going out easily. He flopped along lopsidedly, collapsing every couple of steps. Finally, reluctantly, Cammy raised her hand into the air.

“Can I go to the bathroom?”

She could already feel the rain turning her hair into a giant poof ball. She knelt next to the rabbit. He blinked up at her in fear, trying to hobble away, but only falling over sideways. Cammy volunteered at a wild animal rescue on the weekends, so she had a vague idea of what she needed to do. She tried to ascertain if there were any broken bones, which was kind of hard when a flopping rabbit wouldn’t let you touch it. But as the rabbit rolled onto his left side, she saw his right foot was hanging in the wrong direction. Cammy winced.

Gently, she laid her cardigan over the small creature. He was too weak to protest. She pulled him against her chest, his tiny heart beating warm and hard through the material of her shirt. She carried him back to the school doors, wondering what to do. If she told any of the teachers, they’d make her let him go. There was no way they’d let her bring what was technically a wild animal onto school property.

She tucked the rabbit tighter against her and hurried down the hall to her locker. Opening it, she made a kind of nest, using her book bag and the change of clothes Grandma made her keep there, “just in case.” Lunch was only two periods away. She could get Gramps to come pick up the little guy. “I’ll be back soon,” she whispered, stroking the rabbit’s ear and moving to lift him from her cardigan.

She was surprised when she heard someone behind her. Class was still in session. She quickly held the rabbit to her again, and turned. It was Luke. He was standing in front of the janitor’s closet, which someone had graffittied with two small words in Wite-Out: “Magic Wardrobe.” Since no one had ever seen the door open—it was always locked—the students joked that it hid either Jimmy Hoffa or the gateway to Narnia.

“Are you its mother?” he asked, softly grinning.

“Ra,” she said.

“What?”

Cammy didn’t know why the sound had come out of her mouth. She shook her head. Her stomach had constricted into a painful knot.

“What’re you gonna do with it?”

“Um,” she said breathlessly. “Bandages.” Great. She was speaking in caveman.

He squinted at her, disbelieving. “You know how to bandage rabbits?”

Cammy nodded again. For some reason, an Usher song she’d been obsessed with as a kid popped into her head, “My Boo.”

“Oh,” Luke said. He looked a little unsure of himself. Like maybe he wasn’t sure if he was welcome. “Well”—Luke looked around—“I was just heading to the office to pick something up for Mrs. White.”

“Okay. See ya,” Cammy said, trying to sound as careless as possible.

Luke nodded, confused. “Okay.”

“Oh,” Cammy said, just as he turned away. Usher had finally eased off for a moment. “Hey. Can you . . . not tell?” She nodded her head sideways toward her locker.

Luke looked at her, and his small smile returned. “Yeah, yeah, of course. It’ll be our secret. As long as we can name him Thumper.”

Cammy didn’t know if he was joking or not, but the next moment the bell rang, and everyone poured out into the hall to head to their first class.

She turned to her locker and laid the rabbit gently inside. When she turned around again, Luke had moved down the hall into the throng. Cammy let her breath out, long and slow. She turned just in time to see Martin slam into Donald “The Donald” Clark as he walked past him. “Watch out,” Martin said, half laughing. The Donald fell backward against the janitor’s closet.

After standing straight again and composing himself, The Donald looked like his eyes were tearing up.

“It’s okay, Donald,” Cammy said flatly. It was hard to like The Donald. But she always felt bad that no one else did. “Martin’s, you know . . .” Cammy thought of a slew of words she could use to describe Martin, but couldn’t settle on just one. “Here,” she offered The Donald the pigeon she’d been knitting.

The Donald stared down at the pigeon quizzically. Except for his occasional outbursts of tears, he was generally Spock-like with his emotions. He didn’t smile often, if at all, but he did nod and say, “Thanks, Cammy.”

Cammy gave him a half-hearted thumbs-up and then wistfully glanced down the hall. Luke had already disappeared into one of the classrooms, elusive as ever.

It was just slightly chilly when Cammy got back from the Rescue around eight, after helping the vet on duty tend to Thumper’s leg. Sparkles the dog exploded out the front door as soon as Cammy’s grandma opened it, jumping at Cammy’s legs with a passionate, crooked fury.

Grandma stood in the doorway. She was a petite, white-haired woman, with smooth wrinkled skin that smelled like lilacs. She gave Cammy a kiss on the cheek as she walked inside.

“You must be starving. “ She slid a plate of lukewarm macaroni and cheese in front of Cammy, who nodded a thanks and dug in. “How’s the rabbit?”

“Good.” Cammy tried not to talk with her mouth full, but she was too hungry to slow down.

“You had a good day?”

“Yep,” Cammy said. They’d been doing the same routine for years. No matter how bad her day was, she always lied. She didn’t like to worry her grandparents. They had enough to worry about, with a daughter gone AWOL. They used to tell Cammy that her mom loved her and that she’d come back for her when she’d sorted herself out. Now they never talked about her at all.

“Tell that Hilda to drive slower,” her grandpa boomed from some hidden spot deeper in the house.

“It wasn’t Gerdi, it was Jill from the Rescue, and she drives slower than you do,” Cammy called blandly. He answered with an indistinct grumble. Cammy’s grandpa was always calling Gerdi a vaguely lederhosen-ish name, like Heidi or Hilda, but hardly ever the real one.

After wolfing down a plate of her grandma’s chewy chocolate-chip oatmeal cookies for dessert, Cammy moved about the house, doing chores. This was the routine: chores, followed by watching Jeopardy! with her grandma, organizing her miniature tea sets, and talking on the phone to Gerdi about whatever boy liked Gerdi that day. Nights were usually also accompanied by lectures from Gramps about the dangers of life.

Tonight, she was restless and didn’t know what to do with herself. She walked up to her room and stood before the floor-length mirror, looking at herself. Over the summer she’d hoped she’d look different in time for sophomore year. But she was about the same as she was last year, still hobbitlike at 5 foot 2; still pale, bushy haired, and wide-cheeked. She had once heard that people found symmetry attractive, because if you were symmetrical, it meant you’d produce healthy offspring. It made her frown now at her uneven eyebrows and the fact that the tip of her nose listed a little to the left.

She took a look at her dog, Sparkles. He was sitting on the carpet, licking his lips and staring at her with his bulgy eyes and awkward, crooked chin. Sparkles had the body of a hot dog and the legs of a caterpillar. One eye was brown and the other was blue. He was always disheveled, and it only emphasized how unattractive he was. Sometimes she feared that everyone ended up with the pet that suited him or her best.

She sifted through her collection of Golden Girls, which was her grandma’s favorite show from the eighties and which Cammy watched whenever she couldn’t sleep. But the fall breeze was drifting through the screened window, and she was restless. Her grandparents turned the heat up to eighty as soon as it got cool, like lizards needing to keep a constant body temperature. Cammy kept her windows open so she wouldn’t die of heat exhaustion. Now she leaned against the screen, pressing her face against it and taking a deep breath. Finally, she walked downstairs.

Out on the front porch, she closed the door behind her, breathing in the fresh, cool air and rubbing Sparkles’s ears. She rocked on the rocker—back and forth, back and forth—and listened to the rustle of the leaves.

Somewhere, there was a desert with giant cliffs, and somewhere people were sailing boats and falling in love and going off on adventures and discovering things for the first time, with no time for collecting teapots. She knew this from TV. But Cammy could see herself sitting on this porch, night after night, forever, growing into it like a weed.

Cammy pulled out her cell phone and texted the universe. She dialed a ton of 9s. She wrote, I’m pretty sure nothing is ever going to happen to me. It was something she did sometimes when she didn’t know what else to do. Like Googling why bad things happened to good people. It was an act of faith—that someone out there knew, and understood, and could make things right. And then she stood up and walked back inside to catch the tail end of Jeopardy!

AT 8:45 ON MONDAY MORNING, MRS. WHITE WAS TRYING TO get a handle on her homeroom students. The students’ voices rose loudly above the blaring sound of Channel One, a news show that was broadcasted throughout the school each morning. On-screen, shots of the newscaster were interspersed with commercials about “high school needs,” like dandruff shampoo and matte foundation. Cammy Hall always wondered how they justified subjecting fifteen-year-old girls to watching maxi-pad absorption demos in a room full of fifteen-year-old guys.

Martin Littman sat two seats to Cammy’s right, snickering at the ads, and then grinning at her. He had long curly hair, wet lips, and high cheekbones. He was a complete buffoon, and inexplicably, extremely popular. “Prune juice,” he mouthed at Cammy, because on the first day back to school—two weeks ago—Cammy’s grandma had packed prune juice with her lunch, and Martin—as sharp-eyed as he was dim-witted—had managed to remember this little fact. That’s when Cammy and her best friend, Gerdi, had agreed to resume eating their lunches out behind the school by the Dumpsters, like they had just about every day the previous year.

She glanced over at Gerdi sitting across the room. Gerdi pulled a shiny tube top out of her backpack and waved it at her. She’d shown Cammy the top on their ride into school this morning, and now Gerdi was baiting her with it.

What’s it for? Cammy had asked, trying not to notice how fast Gerdi was driving. Ignoring Gerdi’s carelessness was something she tried to do every time they were in the car, in order to keep her sanity.

Homecoming.

Cammy had sighed pointedly. Gerdi had sighed back in response. It’s not an execution, Cammy, it’s a dance. Gerdi, who was from Denmark, pronounced “dance,” “dunce.” Now she was making the tube top dunce above her bag, smiling at Cammy encouragingly.

Cammy grinned, thinking of how Gerdi always acted so much less sophisticated than she looked. Today she was dressed in a purple, off-the-shoulder T-shirt and a pair of black jeans, with tiny black leather boots her father had sent her from Denmark. Her short brown bob was not pretty, per se, but it was European and striking and only made more of Gerdi’s perfect, wide cheekbones and full, rosy Danish cheeks. She looked like a cross between the little Dutch Boy from those paint cans and the lead singer of the Yeah Yeah Yeahs. Gerdi always looked very cool, even when she was making clothes dance. But Cammy knew better—Gerdi slept with a stuffed platypus, and had recently made a scrapbook called Gerdi’s Book of Hot Guys, like a third grader.

Finally, Gerdi stuffed the top into her backpack, gleeful, obviously excited about the dunce. But then again, for lots of reasons, things were easier for Gerdi.

In front of Cammy, Bekka Bell and her friend Maggie Flay were passing notes back and forth. Cammy glimpsed her name interspersed in the note Bekka opened onto her desk. Well, not her real name. Her nickname. The one she’d been christened with in fifth grade, when she’d gotten the flu and puked up her ham sandwich in the middle of the cafeteria: Hammy.

Gerdi wasn’t nicknamed after pork. That was one reason it was easier for her. For another thing, Gerdi was an outcast only by chance. She was pretty, smart, fun-loving, savvy. Her one mistake was that she had appeared at Browndale during seventh grade, in the middle of the school year, as an exchange student, toting a backpack with a cartoon character on the back, a thick Danish accent, and an arsenal of soon-to be-butchered English phrases. She’d been immediately shunned.

Cammy, on the other hand, was a born outsider. She’d cemented her position at the bottom of the Browndale High School food chain over many years of careful self-humiliation. Wearing a tube top to the homecoming dance was not on the list of humiliations she wanted to explore further. She hadn’t said it to Gerdi, but she’d be willing to bet a hundred dollars that someone would call her a sausage by the end of the night.

It wasn’t just her pudginess. There was her awkwardness with people she didn’t know that well. Also, there was the time she’d gotten her head stuck in between the bars of the gates while peering at the prairie dogs on a trip to the zoo, and the time she had tried to dress up as a sexy Spanish dancer for an eighth grade Halloween party, and everyone had thought she was supposed to be Norman’s mother from Psycho. There was her tendency to drool. And the fact that her eyebrows were eerily identical to Frieda Kahlo’s.

Cammy pulled out her knitting needles and yarn from under her desk, and tried to concentrate on them. Knitting was a skill her grandmother had taught her to make herself feel calm and peaceful. Today, she was working on a small amigurumi pigeon.

In front of her, Bekka ran her hands through her hair endlessly, plucking off the split ends, caressing the strands and working through the tangles, holding her long red hair as if it were gold. Bekka’s hair, which had grown miraculously silky and manelike between seventh and eighth grade, was her pride and joy. Occasionally, she would flick it back completely and it would fly into Cammy’s face or land softly on her desk with a gentle patter. The constant self-worshipping hair stroking always drove Gerdi bananas. From across the room, she was predictably throwing mournful, annoyed looks at Cammy, urging her, with her hands, to pull Bekka’s hair.

But Cammy channeled all of her anger into her tiny pigeon instead. She reflected on her new school year’s resolution. Junior high and even freshman year had been a long string of embarrassing events. But she was determined: This would be her year of living it down. Or, at least, of being completely invisible.

Up front, a Clearasil ad came on. The class watched as an impossibly beautiful girl on-screen agonized over whether the hottie waiting for the bus would see her zit or not. Gerdi was rolling her eyes and sinking back into her chair, pretending to die of American commercialism. Bekka and Maggie were whispering that the nose of the girl on TV was too big. Cammy tried to tune them out, leaned back slightly in her seat, casually turning her head to peer over her shoulder. Luke Bryant was sitting two seats diagonally behind her.

Cammy leaned back a little more. She let her eyes drift to him—first his hands, holding a pencil and twirling it around and around. Then up to his face. He had dreamy hazel eyes and big hands, and he looked like a drummer or something, with finely muscled arms and dark shaggy hair. His expression was inscrutable, his eyes on the ceiling, his mind clearly somewhere else. He laid the pencil down and picked at the spiral of his notebook.

In fifth grade Cammy had transferred her girlhood interest in unicorns to an interest in Luke. Coincidentally, he was like a unicorn in a couple of key ways: He was beautiful and he was completely inaccessible.

Of course everyone is in love with him, Gerdi had said. Love for aloof, inaccessible men was written into the female DNA. Just look at Mr. Darcy from Pride and Prejudice. Or that mean, old blind guy in Jane Eyre. On Monday one of the freshmen had actually cried after Luke had said hi to her in the hallway. The only thing that kept girls from throwing their underwear at Luke onstage was that he wasn’t in any of the plays.

Cammy drifted off, thinking about the old blind guy in Jane Eyre. She couldn’t remember: How had he lost his eyes? Had they been pecked out by a bird or something? Still, he had always sounded miraculously hot, even without eye—

Suddenly she realized Luke’s eyes weren’t on the ceiling, but on the pigeon in her lap. With a quizzical expression, he glanced up and met her eyes, and gave her the slightest hint of a smile. She snapped her head back around, shooting forward so that a tiny piece of spit flew out of her mouth and landed on the back of Bekka’s collar. Mortified, Cammy tried to pull herself together. She didn’t dare look back at Luke to find out if he’d seen. She gazed at the drop of spit sitting on Bekka’s collar, debating on whether or not she’d try to wipe it off.

Up front, Mrs. White was pulling up at her tan stockings for the tenth time. She then started to move up and down the aisles, patting Cammy’s shoulder as she passed her. Cammy shrank under her touch; being one of Mrs. White’s favorites always felt like being a harbinger of doom.

It’s like being in the club of lonely ladies who wear bad outfits and are sad about men, Gerdi had said recently. The scary thing was, Cammy already had the outfits.

Outside, it had just started to drizzle. A stirring drew Cammy’s eyes to the window. There was a movement in the grass. An injured rabbit was flopping away from the road.

Cammy was frozen. She sat and agonized, wondering what to do about the rabbit. She hoped he would just die quickly. But clearly, the rabbit wasn’t going out easily. He flopped along lopsidedly, collapsing every couple of steps. Finally, reluctantly, Cammy raised her hand into the air.

“Can I go to the bathroom?”

She could already feel the rain turning her hair into a giant poof ball. She knelt next to the rabbit. He blinked up at her in fear, trying to hobble away, but only falling over sideways. Cammy volunteered at a wild animal rescue on the weekends, so she had a vague idea of what she needed to do. She tried to ascertain if there were any broken bones, which was kind of hard when a flopping rabbit wouldn’t let you touch it. But as the rabbit rolled onto his left side, she saw his right foot was hanging in the wrong direction. Cammy winced.

Gently, she laid her cardigan over the small creature. He was too weak to protest. She pulled him against her chest, his tiny heart beating warm and hard through the material of her shirt. She carried him back to the school doors, wondering what to do. If she told any of the teachers, they’d make her let him go. There was no way they’d let her bring what was technically a wild animal onto school property.

She tucked the rabbit tighter against her and hurried down the hall to her locker. Opening it, she made a kind of nest, using her book bag and the change of clothes Grandma made her keep there, “just in case.” Lunch was only two periods away. She could get Gramps to come pick up the little guy. “I’ll be back soon,” she whispered, stroking the rabbit’s ear and moving to lift him from her cardigan.

She was surprised when she heard someone behind her. Class was still in session. She quickly held the rabbit to her again, and turned. It was Luke. He was standing in front of the janitor’s closet, which someone had graffittied with two small words in Wite-Out: “Magic Wardrobe.” Since no one had ever seen the door open—it was always locked—the students joked that it hid either Jimmy Hoffa or the gateway to Narnia.

“Are you its mother?” he asked, softly grinning.

“Ra,” she said.

“What?”

Cammy didn’t know why the sound had come out of her mouth. She shook her head. Her stomach had constricted into a painful knot.

“What’re you gonna do with it?”

“Um,” she said breathlessly. “Bandages.” Great. She was speaking in caveman.

He squinted at her, disbelieving. “You know how to bandage rabbits?”

Cammy nodded again. For some reason, an Usher song she’d been obsessed with as a kid popped into her head, “My Boo.”

“Oh,” Luke said. He looked a little unsure of himself. Like maybe he wasn’t sure if he was welcome. “Well”—Luke looked around—“I was just heading to the office to pick something up for Mrs. White.”

“Okay. See ya,” Cammy said, trying to sound as careless as possible.

Luke nodded, confused. “Okay.”

“Oh,” Cammy said, just as he turned away. Usher had finally eased off for a moment. “Hey. Can you . . . not tell?” She nodded her head sideways toward her locker.

Luke looked at her, and his small smile returned. “Yeah, yeah, of course. It’ll be our secret. As long as we can name him Thumper.”

Cammy didn’t know if he was joking or not, but the next moment the bell rang, and everyone poured out into the hall to head to their first class.

She turned to her locker and laid the rabbit gently inside. When she turned around again, Luke had moved down the hall into the throng. Cammy let her breath out, long and slow. She turned just in time to see Martin slam into Donald “The Donald” Clark as he walked past him. “Watch out,” Martin said, half laughing. The Donald fell backward against the janitor’s closet.

After standing straight again and composing himself, The Donald looked like his eyes were tearing up.

“It’s okay, Donald,” Cammy said flatly. It was hard to like The Donald. But she always felt bad that no one else did. “Martin’s, you know . . .” Cammy thought of a slew of words she could use to describe Martin, but couldn’t settle on just one. “Here,” she offered The Donald the pigeon she’d been knitting.

The Donald stared down at the pigeon quizzically. Except for his occasional outbursts of tears, he was generally Spock-like with his emotions. He didn’t smile often, if at all, but he did nod and say, “Thanks, Cammy.”

Cammy gave him a half-hearted thumbs-up and then wistfully glanced down the hall. Luke had already disappeared into one of the classrooms, elusive as ever.

It was just slightly chilly when Cammy got back from the Rescue around eight, after helping the vet on duty tend to Thumper’s leg. Sparkles the dog exploded out the front door as soon as Cammy’s grandma opened it, jumping at Cammy’s legs with a passionate, crooked fury.

Grandma stood in the doorway. She was a petite, white-haired woman, with smooth wrinkled skin that smelled like lilacs. She gave Cammy a kiss on the cheek as she walked inside.

“You must be starving. “ She slid a plate of lukewarm macaroni and cheese in front of Cammy, who nodded a thanks and dug in. “How’s the rabbit?”

“Good.” Cammy tried not to talk with her mouth full, but she was too hungry to slow down.

“You had a good day?”

“Yep,” Cammy said. They’d been doing the same routine for years. No matter how bad her day was, she always lied. She didn’t like to worry her grandparents. They had enough to worry about, with a daughter gone AWOL. They used to tell Cammy that her mom loved her and that she’d come back for her when she’d sorted herself out. Now they never talked about her at all.

“Tell that Hilda to drive slower,” her grandpa boomed from some hidden spot deeper in the house.

“It wasn’t Gerdi, it was Jill from the Rescue, and she drives slower than you do,” Cammy called blandly. He answered with an indistinct grumble. Cammy’s grandpa was always calling Gerdi a vaguely lederhosen-ish name, like Heidi or Hilda, but hardly ever the real one.

After wolfing down a plate of her grandma’s chewy chocolate-chip oatmeal cookies for dessert, Cammy moved about the house, doing chores. This was the routine: chores, followed by watching Jeopardy! with her grandma, organizing her miniature tea sets, and talking on the phone to Gerdi about whatever boy liked Gerdi that day. Nights were usually also accompanied by lectures from Gramps about the dangers of life.

Tonight, she was restless and didn’t know what to do with herself. She walked up to her room and stood before the floor-length mirror, looking at herself. Over the summer she’d hoped she’d look different in time for sophomore year. But she was about the same as she was last year, still hobbitlike at 5 foot 2; still pale, bushy haired, and wide-cheeked. She had once heard that people found symmetry attractive, because if you were symmetrical, it meant you’d produce healthy offspring. It made her frown now at her uneven eyebrows and the fact that the tip of her nose listed a little to the left.

She took a look at her dog, Sparkles. He was sitting on the carpet, licking his lips and staring at her with his bulgy eyes and awkward, crooked chin. Sparkles had the body of a hot dog and the legs of a caterpillar. One eye was brown and the other was blue. He was always disheveled, and it only emphasized how unattractive he was. Sometimes she feared that everyone ended up with the pet that suited him or her best.

She sifted through her collection of Golden Girls, which was her grandma’s favorite show from the eighties and which Cammy watched whenever she couldn’t sleep. But the fall breeze was drifting through the screened window, and she was restless. Her grandparents turned the heat up to eighty as soon as it got cool, like lizards needing to keep a constant body temperature. Cammy kept her windows open so she wouldn’t die of heat exhaustion. Now she leaned against the screen, pressing her face against it and taking a deep breath. Finally, she walked downstairs.

Out on the front porch, she closed the door behind her, breathing in the fresh, cool air and rubbing Sparkles’s ears. She rocked on the rocker—back and forth, back and forth—and listened to the rustle of the leaves.

Somewhere, there was a desert with giant cliffs, and somewhere people were sailing boats and falling in love and going off on adventures and discovering things for the first time, with no time for collecting teapots. She knew this from TV. But Cammy could see herself sitting on this porch, night after night, forever, growing into it like a weed.

Cammy pulled out her cell phone and texted the universe. She dialed a ton of 9s. She wrote, I’m pretty sure nothing is ever going to happen to me. It was something she did sometimes when she didn’t know what else to do. Like Googling why bad things happened to good people. It was an act of faith—that someone out there knew, and understood, and could make things right. And then she stood up and walked back inside to catch the tail end of Jeopardy!

About The Illustrator

Brittney Lee is a designer and animator. She lives in Emeryville, CA.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers (December 21, 2010)

- Length: 272 pages

- ISBN13: 9781416996460

- Ages: 13 - 99

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Loser/Queen Trade Paperback 9781416996460(1.0 MB)

- Author Photo (jpg): Jodi Lynn Anderson Photo Credit:(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit