Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

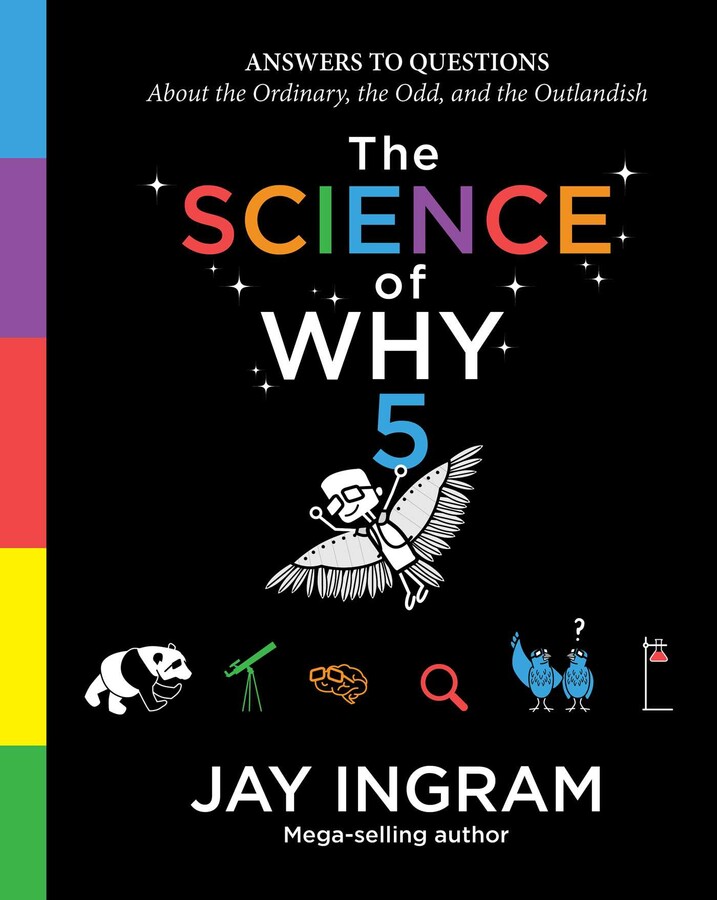

The Science of Why, Volume 5

Answers to Questions About the Ordinary, the Odd, and the Outlandish

Book #5 of The Science of Why series

By Jay Ingram

Table of Contents

About The Book

Chock-full of peculiar puzzles, mind-bending mythbusters, and quirky questions, the fifth pop science book in the bestselling Science of Why series is perfect for anyone curious about the weird and wondrous world we live in.

Have you ever wondered if octopuses are from outer space? What Mexican jumping beans are? Or if banana peels are really slippery?

If questions like these are keeping you up at night, you can rest easy. Bestselling author Jay Ingram is here to answer all the whimsical and whacky wonderings that have baffled people since the dawn of time. From our bodies to our pets (and other beasts) to the natural world around us, Jay tackles science topics big and small, such as:

Did dinosaurs sit on their eggs?

What is our funny bone?

Is there a specific muscle that makes dogs cute?

Because who hasn’t pondered whether plants have feelings? Or if Robin Hood was a real person? Or what humans will look like in the future?

Teeming with amusing answers to bemusing questions—and handy and hilarious illustrations—this latest volume separates fact from fiction, lesson from legend, and myth from marvel. Endlessly illuminating and entertaining, The Science of Why, Volume 5 is five times the fun for new and old readers of the series.

Have you ever wondered if octopuses are from outer space? What Mexican jumping beans are? Or if banana peels are really slippery?

If questions like these are keeping you up at night, you can rest easy. Bestselling author Jay Ingram is here to answer all the whimsical and whacky wonderings that have baffled people since the dawn of time. From our bodies to our pets (and other beasts) to the natural world around us, Jay tackles science topics big and small, such as:

Did dinosaurs sit on their eggs?

What is our funny bone?

Is there a specific muscle that makes dogs cute?

Because who hasn’t pondered whether plants have feelings? Or if Robin Hood was a real person? Or what humans will look like in the future?

Teeming with amusing answers to bemusing questions—and handy and hilarious illustrations—this latest volume separates fact from fiction, lesson from legend, and myth from marvel. Endlessly illuminating and entertaining, The Science of Why, Volume 5 is five times the fun for new and old readers of the series.

Excerpt

1. Are octopuses from outer space? Are octopuses from outer space?

IN 2018, THIRTY-THREE SCIENTISTS published an article in the journal Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology arguing that octopuses are actually alien life-forms that arrived on earth on a space rock 270 million years ago.

Yes, you read that correctly.

And, yes, it’s as crazy as it sounds. Octopuses are unique is so many ways that one scientist has said, “It’s like meeting an intelligent alien”—but he didn’t mean that literally.

This theory is an attempt to explain why the octopus is so different, especially genetically, from even close relatives like the chambered nautilus. But it’s not just about the genes: octopuses have a bit of an alien look. They’re also extremely smart, can change pattern and color to blend into their surroundings, and each of their eight arms has its own brain. That last fact alone puts the octopus in a class by itself.

Octopuses have a legendary ability to escape aquariums. They can use tools and solve problems, and they seem able to think in an almost humanlike way. One well-known experiment tested octopuses on their ability to open a complicated set of boxes to get at a crab treat inside. The first box had a latch that needed to be twisted open; inside that was another box, which slid to open; and that in turn was inside a third box, which had two different locks. Two or three trials was all octopuses needed to be able to open all the boxes in three or four minutes.

What makes an octopus so smart? Its nervous system has 500 million neurons, ranking it somewhere between the European rabbit and the western tree hyrax, an African guinea pig–like animal. But the number of neurons alone isn’t a good measure of intelligence. The way those neurons are organized is important, too, especially in the octopus.

Of the octopus’s 500 million neurons, 150 million are found in the brain, and the other 350 million are shared among the arms. In effect, each arm has its own minibrain and is capable of making its own decisions. If one of the suckers detects something delicious, for example, that arm will alert the other arms to what’s happening. Then the arm will curl around the food, making a kind of hand, while the rest shapes itself into an upper and lower arm and an elbow so that the “hand” can bring the food to the mouth.

Science Fact! Eerily, an arm that’s been separated from an octopus’s body will still grab food and try to pass it to where the mouth should have been. It will also try to crawl away on its own.

What sets octopuses apart? The chambered nautilus, a cousin, is not nearly as intelligent. Some experts think the key difference is that the nautilus never lost its shell. It leads a relatively safe and lengthy life (it can live up to twenty years), but perhaps not the most exciting one. The octopus, on the other hand, lost that shell completely as it evolved into its modern form. The argument is that losing the protection of the shell put evolutionary pressure on the octopus to become smart, agile, well camouflaged, and capable of squeezing into the tiniest spaces. The trade-off is that it typically survives only two or three years in the wild.

All of these features make the octopus an extraordinary creature, but the scientists arguing for its alien origin concentrate only on its genes. Genes build animals, but octopuses do it in a different way. They are genetically nimble and can apparently alter the way their genes are expressed, allowing them to respond rapidly to changes in their environment. But that nimbleness reduces the octopus’s ability to fine-tune its DNA over longer periods of time, the process that drives evolution. This machinery is not unique to octopuses—we humans have it, too—but in most other species, it’s a tiny feature of the genome, whereas in the octopus it is absolutely crucial.

That brings us back to the “octopus as alien” theory. The argument is that this ability to revamp the genome is not typical of other animals on Earth—therefore octopuses must have come from space. They would have arrived not as full-grown animals but as frozen octopus eggs. It would be pretty cool if it were true, but the evidence isn’t exactly airtight. It may look like the octopus appeared out of nowhere 270 million years ago, but there are so few octopus remnants in the fossil record that it’s impossible to be sure. And while their practice of gene editing is intriguing and unusual, does the fact that we do it, too, mean we come from space as well?

If you still want to believe that octopuses are aliens (and I wouldn’t blame you if you do!), you should know that for decades now the authors of this paper have been pushing the idea that life arrived on earth from space. All life, that is. So far they haven’t been able to persuade the rest of the scientific community of that.

IN 2018, THIRTY-THREE SCIENTISTS published an article in the journal Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology arguing that octopuses are actually alien life-forms that arrived on earth on a space rock 270 million years ago.

Yes, you read that correctly.

And, yes, it’s as crazy as it sounds. Octopuses are unique is so many ways that one scientist has said, “It’s like meeting an intelligent alien”—but he didn’t mean that literally.

This theory is an attempt to explain why the octopus is so different, especially genetically, from even close relatives like the chambered nautilus. But it’s not just about the genes: octopuses have a bit of an alien look. They’re also extremely smart, can change pattern and color to blend into their surroundings, and each of their eight arms has its own brain. That last fact alone puts the octopus in a class by itself.

Octopuses have a legendary ability to escape aquariums. They can use tools and solve problems, and they seem able to think in an almost humanlike way. One well-known experiment tested octopuses on their ability to open a complicated set of boxes to get at a crab treat inside. The first box had a latch that needed to be twisted open; inside that was another box, which slid to open; and that in turn was inside a third box, which had two different locks. Two or three trials was all octopuses needed to be able to open all the boxes in three or four minutes.

What makes an octopus so smart? Its nervous system has 500 million neurons, ranking it somewhere between the European rabbit and the western tree hyrax, an African guinea pig–like animal. But the number of neurons alone isn’t a good measure of intelligence. The way those neurons are organized is important, too, especially in the octopus.

Of the octopus’s 500 million neurons, 150 million are found in the brain, and the other 350 million are shared among the arms. In effect, each arm has its own minibrain and is capable of making its own decisions. If one of the suckers detects something delicious, for example, that arm will alert the other arms to what’s happening. Then the arm will curl around the food, making a kind of hand, while the rest shapes itself into an upper and lower arm and an elbow so that the “hand” can bring the food to the mouth.

Science Fact! Eerily, an arm that’s been separated from an octopus’s body will still grab food and try to pass it to where the mouth should have been. It will also try to crawl away on its own.

What sets octopuses apart? The chambered nautilus, a cousin, is not nearly as intelligent. Some experts think the key difference is that the nautilus never lost its shell. It leads a relatively safe and lengthy life (it can live up to twenty years), but perhaps not the most exciting one. The octopus, on the other hand, lost that shell completely as it evolved into its modern form. The argument is that losing the protection of the shell put evolutionary pressure on the octopus to become smart, agile, well camouflaged, and capable of squeezing into the tiniest spaces. The trade-off is that it typically survives only two or three years in the wild.

All of these features make the octopus an extraordinary creature, but the scientists arguing for its alien origin concentrate only on its genes. Genes build animals, but octopuses do it in a different way. They are genetically nimble and can apparently alter the way their genes are expressed, allowing them to respond rapidly to changes in their environment. But that nimbleness reduces the octopus’s ability to fine-tune its DNA over longer periods of time, the process that drives evolution. This machinery is not unique to octopuses—we humans have it, too—but in most other species, it’s a tiny feature of the genome, whereas in the octopus it is absolutely crucial.

That brings us back to the “octopus as alien” theory. The argument is that this ability to revamp the genome is not typical of other animals on Earth—therefore octopuses must have come from space. They would have arrived not as full-grown animals but as frozen octopus eggs. It would be pretty cool if it were true, but the evidence isn’t exactly airtight. It may look like the octopus appeared out of nowhere 270 million years ago, but there are so few octopus remnants in the fossil record that it’s impossible to be sure. And while their practice of gene editing is intriguing and unusual, does the fact that we do it, too, mean we come from space as well?

If you still want to believe that octopuses are aliens (and I wouldn’t blame you if you do!), you should know that for decades now the authors of this paper have been pushing the idea that life arrived on earth from space. All life, that is. So far they haven’t been able to persuade the rest of the scientific community of that.

Product Details

- Publisher: Simon & Schuster (November 10, 2020)

- Length: 208 pages

- ISBN13: 9781982140854

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Science of Why, Volume 5 Paper Over Board 9781982140854

- Author Photo (jpg): Jay Ingram (c) Richard Siemens(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit