Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

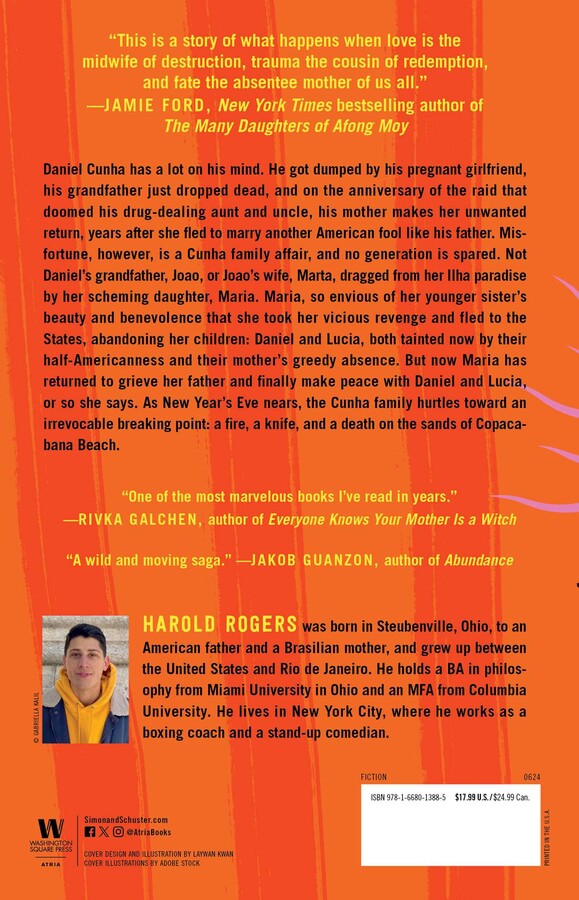

About The Book

Daniel Cunha has a lot on his mind.

He got dumped by his pregnant girlfriend, his grandfather just dropped dead, and on the anniversary of the raid that doomed his drug-dealing aunt and uncle, his mother makes her unwanted return, years after she fled to marry another American fool like his father.

Misfortune, however, is a Cunha family affair, and no generation is spared. Not Daniel’s grandfather João—poor João—born to a prostitute and forced to raise his siblings while still a child himself. Not João’s wife, Marta, branded as a bruxa, reviled by her mother, and dragged from her Ilha paradise by her scheming daughter, Maria. And certainly not Maria, so envious of her younger sister’s beauty and benevolence that she took her vicious revenge and fled to the States, abandoning her children: Daniel and Lucia, both tainted now by their half-Americanness and their mother’s greedy absence.

There’s poison in the Cunha blood. They are a family cursed, condemned to the pain of deprivation, betrayal, violence, and, worst of all, love. But now Maria has returned to grieve her father and finally make peace with Daniel and Lucia, or so she says. As New Year’s Eve nears, the Cunha family hurtles toward an irrevocable breaking point: a fire, a knife, and a death on the sands of Copacabana Beach.

Amid the cacophony of Rio’s tumult—rampant poverty, political unrest, the ever-present threat of violence—a fierce chorus of voices rises above the din to ask whether we can ever truly repair the damage we do to those we love in this “fiery debut novel” (The Washington Post).

Excerpt

CALL ME DANIEL, I was telling the american girls. Mateus met them this morning and asked me to pull up, thinking I needed a rebound after his cousin dumped me. So the four of us were out here chilling under the hard sun, the sun mean like it was trying to scorch us into order. The turista girls shining pretty, soaked in the day’s slow progress. Our kiosk watched by the bronze frozen gaze of Princesa Isabel, the statue the police were all posted under, cradling their machine guns like gifts for the people. Sweeping the beach with their military stare. But how could you sweat that? With the pigeons all plump, plopped weary on the calçadão cobblestones, with those malandra vultures circling their black spirals in the sky, with the kiosk cover band batucando nice?

Copacabana was bustling!

The muvuca all crowded around to hear the band go into País Tropical.

Eu moro! num país tropical!

And I couldn’t help but think of my Leticia. Who wasn’t mine anymore. Because she dumped me yesterday. For cheating. Or not listening. Or something.

Anyway, I asked the girls where they were from.

Rachel, who had ferocious green eyes and was smiling at me in a way I could get behind, said, We’re from Pittsburgh, we go to college around there.

Her sister Olivia said, No we’re not. We’re from like forty minutes outside of Pittsburgh.

I said Pittsburgh so he would have an idea! You can’t expect him to know our geography.

But don’t lie to him!

My geography is pretty good. I lived in the States. That’s why my english is so much better than Mateus’s.

Vai se fuder porra!

Rachel said, What were you doing there?

Living with my dad.

What happened?

He died so I had to leave.

Oh my god, Olivia said, I’m sorry.

It’s ok.

Rachel said, Our mom died too. Well, not too, but. She died eight years ago.

Of what?

Cancer. How bout yours?

She seemed breezy enough with death, so I said, Guess.

Suicide?

I started cracking up, Jesus!

You told me to guess!

It was a car wreck, so close, I guess.

We both started laughing. I took a long drink from the beer in front of me. We were strangers who just hit a nice laugh. I had to temper this moment so her high fun expectations wouldn’t crash on me later.

Olivia asked Mateus, How did you and Daniel meet?

Futebol, we played juntos over there by the Palace. He pointed out into the distance. Daniel was so bad. Pernas de pau we say here, wooden legs.

I flipped him off and said, Fuck you, in his accent.

We moved here mermo tempo.

Same time. Summer 2006. We were both a little out of place here, so we bonded quick.

Tell them about the license plates.

There was this dude who used to hang around the fields running these little schemes. And we would help him out. Mateus started first but he was scaring turistas off, couldn’t get nobody to trust him. So I started helping out because I got a friendly face, you know. We would walk around with these Rio vanity plates and we would say, Give us half the money now and then tomorrow we’ll meet you with whatever you want written on it. And then you just didn’t show up. It was easy. Until one day these french fuckers I scammed ran into us, demanding their money back. And Mateus in a courageous enthusiasm punched one of the dudes right in the face.

Wow! And then what happened?

They beat our ass and got their money back!

Mateus and the girls cracked up. Mateus hawing and slapping the table.

But after that we were like best friends.

Verdade!

The table got quiet.

I waved over another round of beers from the kiosk guy, thinking about when this shit used to be a lot cooler, cheaper. When me and Leticia were real young and haunted these places. You had the dudes back then who actually owned and ran their own shit, every kiosk a solid blue or green or yellow with the flimsy plastic chairs out in their orbit on the calçadão. Coconuts studded on the kiosk roof like it was jeweled up.

Now you couldn’t even get a coconut broke open! They drilled a bullshit hole in it and sometimes even poured the water into a plastic cup. Lame! The best part used to be when you were done. You’d take it to the dude and he’d get that big butcher knife out and split it in two, giving you the halves and a little husk spoon you’d use to scrape the meat off. Now the kiosks were all owned by Nestlé or some shit. So we almost always dipped without paying. Our little rebellion against the state.

Rachel’s purse was splayed out on the table, tossed all strewn like she stole it.

She grabbed it and pulled out a pack of Marlboro Reds.

I would die for a cigarette right now.

It doesn’t have to be that serious, she said, handing me one and a lighter.

The beach breeze hit, bringing that fishy maresia and the gaivota smell, cooling the sweat on the back of my neck. I leaned down and cupped the cigarette close to light it and took a deep inhale. My mom used to smoke Marlboro Reds, so that smell was embedded in the cramped and hot walls of my memories from the Ilha. That loud little house. That loud, violent little house.

So why’d you guys come here? I asked Olivia, trying to spread the conversational duty.

Our step mom is from Brazil. She said it would be cheap and hot.

Certainly cheap if you got dollars.

Your mom carioca? from Rio?

Mateus said Rio in portuguese, it flowed from his mouth easy. I americanized it when I spoke english, drawing out that R, like I was climbing over a hill.

I don’t know. I don’t listen to half the shit she says. She’s the worst.

Don’t say that.

What Rachel, now you don’t think she’s a bitch?

Some real tension sparked up between them, like Rachel wasn’t defending the worldview they agreed to present to the public. It got awkward. I just smoked my cigarette and drank my beer, looking out at the green hills in the distance and the pulsing sea. Wishing this miserable heat would let up. I needed another drink.

Olivia pulled out her phone so she wouldn’t have to talk, a big iPhone she shouldn’t be flaunting around. I pulled my phone out too, uncomfortable resting in the silence. I scrolled through whatsapp. There were some guys that stayed sharing the goofiest shit, just spamming. Like this nerdy hermetic kid that I hadn’t talked to since high school, Kleber. He sent a video captioned with horrified scream emojis, and I clicked it. My morbid curiosity winning over my tact. It opened up on a dude in a red sunga, standing on the roof’s edge of the hotel right next to the Marriott, right over there by my grandma’s place. He was clinging to the edge, precarious as hell. The camera zoomed in, slowly swaying back and forth. Suddenly he takes a big olympic style leap, arms out and everything, right off the building. The guy filming it goes, Meu deus meu deus meu deus, and runs toward him. The video ends.

I closed out of it quick, my breath tight, hoping nobody saw me see that.

Like it was something dirty. Something rotten in Copacabana.

The despair was thick these days. People without shit to do, no job, no purpose.

Like I was one to talk.

But jumping off a building?

Grandma used to say that a suicide would relive the moment of their death again and again and again until the end of time. That it was the worst hell you could imagine. Peeking down at that interminable abyss. Your body cutting through that light air, feeling no resistance. Until the ground stopped you dead. Over and over and over. Good reason not to do it. Grandma stuck working at the supermarket bagging groceries all day, newly widowed. All her daughters gone. I wondered if that’s what kept her around, bearing time and those brutal scorns, knowing that the undiscovered country she’s heading to might not be filled with light but with endless misery. I could see why you’d do it. It looks like an answer. No more grunting and sweating under this heavy life. All your problems solved. Like magic. Gone.

Grandma, grandma, grandma. She hadn’t even called me since grandpa died two days ago. Well, why would she? I hadn’t been home in weeks. She probably thought I didn’t wanna hear from her. I only got the news because my sister Lucia texted me. I didn’t respond. But her birthday was yesterday, and I was feeling the pangs of being a bad grandson and brother and all that, so I texted her. So our text chain looked like

grandpa died

happy birthday

with no responses in between.

Mateus was going, Daniel, ô Daniel!

I must’ve zoned out. The girls were looking at me. Rachel with those eyes.

What’s up?

As minas wanna do things.

Oh yeah? Wanna go see the Christ?

Rachel got quiet and looked away. Olivia kinda mumbled something.

Mateus said in portuguese, Dude, an american family got killed there like two days ago.

How bout the Pão de Açúcar then? It’s a hundred percent safe!

Cobrinha’s working.

Perfect. We can get in for free. How does that sound?

Rachel said, Sounds good to me.

That smile of hers!

I was the only one who asked for another beer and as soon as the waiter set it down, I chugged it. I think Olivia was gonna do the same thing with the last drops of her drink, but as her hand reached for it, she knocked it over, splashing beer all over Mateus’s jersey. The sacred Zico jersey his father had given him right before he died. To make matters worse, Flamengo was in the world championship today. All Mateus had to do for them to win was keep the jersey clean and not watch the game. Porra! His relic on the day of the world championship, tainted.

But Mateus never lost his cool.

Ahh, he said. Merda.

Olivia was apologizing profusely and trying to dry up the mess with the weak and useless table napkins, but it was like trying to towel yourself off with a plastic bag. Mateus said, It’s ok. But I knew in his mind he had let down his dead father and Zico, and that this was a terrible omen portending a Flamengo loss, if not worse.

Rachel threw in an apology too.

It’s ok. Tá tudo bem.

Let’s fucking vambora. Grab your stuff. We’re gonna run.

The girls rounded up their things in a hurry. The lone waiter was busy taking out the trash, everyone else distracted by the band.

Go! I yelled.

We took off across the street, toward the bus stop.

MY FLIPFLOP came undone while I was running so I was fixing it hop crossing the street. One bare foot hot on the asphalt. The military police were set up makeshift right out front of the hotel. They watched us as we crossed, making sure we weren’t dangerous, wondering why we were running. Police had always been everywhere, but not like this. We were drowning in them. And since it was two days until New Year’s Eve, they were ramping it up. Like they were expecting some shit to finally pop. For the lid to blow off this carioca pressure cooker.

So they couldn’t leave a corner of the city ungripped by their brand of safety.

My flipflop was working again by the time we got to the bus stop. Everyone standing around waiting, waiting, waiting. That patient Sunday crowd derretating in the heat. This shit would get too hot one day. The sun would incinerate Copacabana. Scorch all of Rio. Leave a pile of ashes of all the generations that stepped foot here and the rain would come and batter us. Make us a part of the soil. That’s what I was thinking while the girls were standing around kinda sheepish. Not talking much and not on their phones. Probably wary of the bus stop crowd.

I asked Rachel what was good.

I’m a little nervous about taking the bus.

We never take the bus back home, her sister added.

Rachel was wearing a Pittsburgh Pirates shirt that she threw on over her bikini. Olivia’s shirt said Franciscan University. They looked very american in a way I reluctantly found attractive. Something of a confused saudade in me for that seven months with my dad. For that cushy, seasoned life.

I mean, worst case scenario is that we get robbed or kidnapped or die in a fiery accident.

Mateus laughed. Don’t assusta them!

I’m playing. I’ve only been robbed on the bus once, on the way to a Vasco game. But that’s the 473. It happens.

Vasco’s his team. Uma merda, they suck. Not worth getting robbed over.

Rachel laughed a little.

Our dad just told us it’s dangerous.

Well, these drivers are bored lunatics. I mean stewing in this heat and traffic all day would make anyone crazy. One time I saw a guy standing too close to the street, and the bus came and clipped him, mangled the dude.

They looked at me.

Which is to say we’re probably safer actually riding the bus.

That ended that conversation, leaving us quiet. Standing around sweating. There were probably ten other people waiting with us. One guy was looking at me. Staring. Tall with a thick black beard and dark eyes. Looking like a portrait of Cabral come to life. Come back to reconquer this country. Or looking like. Nah, nah, couldn’t be. But he was just staring at me. In a way that made my stomach go cold. I had to turn the other way before I did something that would put a stop to our fun.

After a dead twenty minutes, the bus pulled up. Mercy! Because we could’ve been stuck here another hour easy, and that would’ve sundered all our built up momentum with the girls. Exhausted all possible conversation.

I guess Mateus was up on the fare increase and let the girls know because they had exact change ready. Meanwhile I was held up for ten more cents, 4.30! Ridiculous.

This greedy city and its little catastrophes.

Bora turista! Mateus yelled.

The driver gave me my change and I went to the very back. Mateus and Olivia had slid in to one pair of window seats and Rachel had slid in to the other side, leaving a spot open for me next to her. The driver sped off and I knocked into Rachel. She laughed and helped me balance as I sat down. No AC on this bus so it was tomblike. Our death suspended here in the stagnant passenger smell. But the closed grave heat made the window breeze feel like a blessing when it hit your face, like the air wanted to personally relieve your misery.

Rachel pulled out her phone and started scrolling through instagram.

I was willing myself not to sweat through my shirt.

What’s your IG?

Don’t have one.

Why?

Well, my mom left like six years ago, and she was always trying to hit me up after that. But I didn’t want anything to do with her so, on a whim, I deleted everything. Couldn’t stand her trying to talk to me.

Where did she go?

Ran off to the States to marry some fool. I don’t know much about it.

Sorry. That sucks.

It’s how it goes. Some people can’t wait to get outta here, take any chance they get.

Rachel wanted to cut my drearytalk short, so she said, I love it here so far, Rio is one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever been.

I wanted to say, You’d get used to it fast. You’d be begging for a break from this infernal city in two weeks tops.

But I just said, Yeah, it’s really pretty.

Do you have a girlfriend?

Nah, no. I don’t.

Now’s the time when I should probably tell about Leticia. Leticia! She dumped me yesterday. Which is a bummer because she’s Mateus’s cousin, so I’ll have to see her all the time. They live together with Leticia’s mom, the incomparable Dona Isabel. Who let me sleep on the floor of their tiny thirteenth floor apartment every other day for the past few years. It had been every night lately, which meant I didn’t have a place to stay now.

But she’d take me back. She’d take me back.

Leticia!

I mean, we’d known eachother since we were kids, since we were nine years old. The day we met is my favorite memory. The summer I moved here. Me and Mateus were at a festa junina at the Santa Teresinha church, right by Rio Sul, playing a crushed up can game. Barefoot in the courtyard, flipflops for goalposts. You know how it is.

I was trying a Ronaldinho elástico to get around Mateus, and all of a sudden I heard a voice that stopped my heart in the gap of its beat.

Can I play?

And there was Leticia, dressed caipira with a polka dot shirt, cheeks all jestly freckled, a straw hat barely capping her wild lion’s mane of hair, always untamed.

Her dark brown eyes hit me like lightning.

That’s my cousin, Mateus said.

She joined our game and I’ve been in love with her ever since. The day before I left to go live with my dad, we went to the beach and shared a joint. She kissed me in the water. My first kiss. Iemanjá giving us her blessing. Then I came back and we’d been dating on and off ever since. She even got me going to college with her, UERJ, which because of the bankrupt state and the constant strikes, neither of us might ever graduate from. Which sucked for Leticia. I mean, I probably wasn’t gonna graduate anyway, but she was smart. Crazy smart.

Leticia!

Anyway, she dumped me, not for the first time.

But now she was pregnant, so I needed to fix this.

I was sure she’d take me back.

The bus was stopped at Rio Sul, near the church where I met Leticia. I gazed at it longingly, looking past Rachel who was also peering out the window. And when I looked up there was an old couple walking to the back of the bus. A hunched, withered woman and a man who looked exactly like my grandpa, with a wrinkled, sunbeat face and soft eyes, shuffled slowly to the back of the bus. Exactly like my grandpa would shuffle around our house in his late stage cirrhosis. I remember when it was just me and him all alone in that haunted apartment. He’d be asleep and I’d go to the edge of his room just to stand there, listening to see if I could still hear him breathe, listening to make sure he was still alive. I was always waiting for that last moment. That last grating gasp for breath.

The woman helped the man down the steps, slow, slow. She was sturdier than him, betraying her hunch. But just as he barely set a foot safe on the ground, the bus took off, the door still open. The man yelled, Porra! exactly like my grandpa if Vasco had just got scored on. It was like I was a child looking in the room where he sat putting away beer after beer while I watched this woman hug the rail with one arm and hold on to her husband for dear life with the other. He was dangling off terrified, shoes scraping the road. Everyone on the bus was screaming and so the driver finally stopped after having dragged my grandpa for about a hundred meters.

If his wife’s grip had slackened an inch, he would’ve been flattened dead.

She was breathless after the bus stopped, trying to compose herself. But my grandpa with newfound mental and physical vigor stepped back on the bus and yelled, Vai toma no cu porra! to the driver, and then stepped off with his wife, the two of them clutching eachother tight.

Someone yelled, Idiot!

Another yelled, Psychopath!

And we were back on the road.

But I was shaken and troubled by what I had seen. How much that looked like my grandpa. The anguish on his face. I looked around at the people who were with me, having forgotten they existed. Everyone looked bewildered. Mateus said, Caralho mano.

That was that. We went on.

Rachel, in her fright, had scooted close and grabbed my hand. Which was good. But this was the second terrible omen of the day. If I had been alone I would’ve stepped right off this bus, but I didn’t wanna look weak to these girls, to Rachel.

Besides, my time was meaningless. I had nowhere else to go.

WE WERE the last ones on the bus as it drove through Urca trafficless and pulled into the Pão de Açúcar lot. You could see those two big hills connected by cable cars against the blue backdrop of the clear beach sky. The Vermelha beach sitting tranquil in between. The sea, the sea, stretching out endlessly. The whole vision looking like a postcard.

But the lot was empty. The beach was basically empty.

Not once had I ever pulled into this lot where it wasn’t stuffed full of turistas and paddle boarders and people out here chilling, checking out the maritacas and turtles. But today, nobody. A few soldiers out front of the inescapable military barracks doing their exercises, practicing their shouts, but that was it.

Is it open? Rachel said.

Yeah. Probably just empty because of the game today.

I didn’t believe what I told her. I was disturbed.

Maybe that family getting murdered at the Christ had scared all the turistas off. I never heard of that happening before in such a famous public destination. Maybe it sent out a signal to these outsiders that their mere presence poked the open wound of these disparities. You couldn’t just have all this shit around people who didn’t have shit and not expect any consequences.

But really, I didn’t have a clean explanation.

We stepped off the bus, the soldiers watching us. As we walked up to the uncrowded entrance, hearing the birds singing and the soldiers counting, I felt like I had missed the rapture. Like this place was bustling and teeming just moments ago and then suddenly the saved were plucked up, leaving we the damned behind to taste the remnants of their last breaths in the wind. I looked to my left and had to keep myself from yelping horrified at what I saw.

In the middle of the parking lot, cooking, baking under the impossible sun, was a dead turtle. A big turtle, the type that would swim right up to you at this very beach, leave you smiling for the rest of the day. And there it was, splayed out, defeated. Like it had tried to crawl toward freedom and failed. Leaving a flat husk as the last mark of its life, covered with ants, getting sniffed at by the parking lot pigeons until an ugly vulture flapped in and scattered them.

No one else saw it and I was silent.

Mateus’s cousin Cobrinha was waiting for us at the entrance. They weren’t actual cousins, but that’s what they told everybody. He slithered over to us languid and cool, his usual mode. He dated Leticia in one of our off periods. Cobrinha was very good looking, charming, and very nice. Plus he had tattoos on his face and they say he killed a couple dudes back in the day. Which made me feel shitty about myself. Not that I wanted to kill someone, but it might have added some different kinda credence to my life. Some different kinda credence to the man I wanted to be. I couldn’t help but think that Leticia wouldn’t have dumped me if I was a cool handsome murderer. Cobrinha dumped her because he realized he was gay.

And he was so tactful about it!

Which infuriated me, knowing how much courage and courtesy I lacked.

I tried to be a serious criminal once. When I was about fifteen, a couple years before my aunt Nara went to prison, at the peak of her and my uncle Antonio’s business. Me and Mateus were selling weed for them for pocket money. Antonio didn’t really want us doing it. He always drilled into my head that his life wasn’t an exemplary one, but it was hard not to admire. He was rich, he had swagger. He was a big time drug dealer and people did what he said. He had respect. And my father was dead.

How wasn’t I gonna look up to Antonio?

But so Mateus came across a gun he didn’t really wanna use or buy ammo for so I said let’s put it to some use in an easy way. Tranquilo. We went out stalking around Rodolfo Dantas late, waiting to see if somebody would come up the back way to the Palace.

Sure enough a few hours later here comes this couple talking loud in english. We creep up behind them until they turn the corner and then I make the move. I put the gun on the guy’s back and say, Money now! Mateus is backing me with a little knife in his hand. The couple turns around slow and calm and the woman starts rifling through her purse saying she’s gonna get the money. But instead she pulls out a can of pepper spray and nails us. We go down. They kick us and run off. I told Antonio about it and he chewed me out. I wasn’t cut out for that life, and I got pissed that he recognized that softness in me. So I avoided him after that. Participated in my mother’s doom rooting. Saying they weren’t shit and that it would all come crashing down. Which I felt awful about after the police raid, after everything that happened.

Fala molecada! Cobrinha said. He gave everyone a hug, the girls a kiss on each cheek.

Mateus said in portuguese, Why’s it so empty?

I don’t know man, weirdest day I’ve ever seen here.

Mateus shrugged and Cobrinha started talking to the girls in his basic school english, which really might’ve just been portuguese, but like Mateus, he had a supernatural ability to chat it up with people regardless of language, regardless of where they came from. In seconds, he had the girls cracking up. They didn’t include me in the chitchat so I looked around.

It turned out we weren’t the only people here.

There was a family at the ticket counter. At first glance, I thought it was Cabral from the bus station, those dark eyes, that black beard. But then shockingly, he transformed into somebody else. I swear I felt like my grandma sometimes, seeing ghosts. But I never believed that spirit stuff, that silliness was for Lucia to indulge. It was just my eyes playing tricks on me, because this dude was blond, clean shaven.

It had to be a german turista. With his wife and some strudel ass kids who were making faces and stomping their feet while their dad tried to talk to the ticket lady in some common language of commerce. They were all wearing ridiculous I RJ shirts. I mean, when were the brasilians making this shit gonna realize that nobody outside Brasil associates RJ with Rio de Janeiro? They’re just gonna think these fools love some motherfucker named RJ!

One kid caught me staring and stuck his tongue out. I felt some violence flare up. But I was probably just sensitive toward any germans since that terrible, terrible game. The seven to one. I remember watching it in my grandparents’ room, the summer after Nara got arrested and my mom left. Watching it on our lone, tiny TV when my dad’s house had four. Me and Lucia sitting on the floor, my grandparents on the bed with my little cousin Marta laying in between them. After the fifth goal Lucia and grandma were crying and my grandpa got up and pushed the TV over and broke it. Without Nara there to buy us a new one, we didn’t watch nothing for a while. That game was like a turning point. As if Germany’s goal scorers dead stopped Brasil’s whole growth and knocked us into a regressive crumbling spiral. But maybe kicking this kid’s ass would make up for all that.

Ô Daniel! Mateus was saying. They were all looking at me.

They almost caught me making a face to that little asshole.

Bora ou não?

Let’s go!

We walked through the lobby museum. Black and white pictures of old Rio, people standing proud next to rickety cable cars. I couldn’t believe they not only charged for this, but actually convinced people to ride! I’m sure some people died, trying to heft it together, but this was an international attraction now. So what if it took some blood! Who cares if you gotta sacrifice some brasilian bodies! As long as we can get turistas frolicking up in our space.

We made it to the bondinho boarding zone. There was a ticket girl bored on her phone, but she lit up as Cobrinha came through and let us in no worries. He dropped us off and said goodbye, he had some work to do. He kissed the girls on both cheeks and did the same to me to get a laugh, and then he was off. Of course, we had to wait a moment for the german family who came bumbling through, bickering in their gruff language.

We all boarded the bondinho. There was probably room for twenty more people, I mean, this thing was as big as Dona Isabel’s apartment. But it still wasn’t big enough to keep away those nazilooking kids who were buzzing around like dengue mosquitos. The boy who stuck his tongue out at me had his face pressed up against the window, slobbering against the glass. I knew street dogs who behaved better. No son of mine would ever act like that, me and Leticia would straighten his ass out. Me and Rachel met eyes and caught sight of the girl laying on the filthy carpet throwing a fit while the dopey father took pictures and his wife looked at her phone.

I hate kids, Rachel said. What’s worse than being a mother?

But isn’t the whole point of this dumb thing to kinda keep it going?

She looked at me.

Or not.

So what is there to see up there?

For one, micos. These thieving little monkeys that live up there. They’ll come right up to you and take food out of your hand. They’re too cute.

Mateus heard that and said, São malandra demais!

Now I’m excited.

The bondinho rose higher and higher as the day wound down in the city around us. The sun dipped as we rose, floating over the dense forest that looked sinister as the day changed. Everything was looking sinister to me. But the sun enveloped Rio in a way where it really did look noble, like this city really was marvelous.

Mateus was playing tour guide, showing the girls all the sights and whatnot, making them oooh and ahhh. I was standing in the middle of the bondinho, not looking at anything, thinking about how long it had been since I’d been here. Probably not since high school.

The first time I ever came here, we were still living on the Ilha. Dad was in town on one of his rare trips to visit us and he rented a car so we wouldn’t have to take that long, dull bus ride. Lucia stayed home. Like she usually did. So it was just me, mom, and dad. By the time we got to the second hill, they got in such a savage screaming match that the cops had to come break it up. They kicked us out. My mom told him to go fuck himself and we took the bus just to spite him. Well, she was spiting him. I was just an extension of her will.

The german kids were having a screaming contest as we pulled into the first hill.

Right off the bondinho, the first thing you see is an H.Stern jewelry store. In the window they got these tacky, expensive, decked out toucans and maritacas and papagaios that I couldn’t fathom attracted any customers with voluntary control over their actions. So of course, testing the limits of free will, the german family strolled right in, cooing at how pretty the birds were.

Rachel and Olivia were standing around like where to? The sun was gonna set soon and I knew a place where the view would be serious. This little manmade bamboo grove where you could cut through and be free on the hillside. I found it by accident when I was a kid, wandered over there while my parents were fighting. Years later that’s where I would take girls from school, or girls I was seeing extracurricularly.

Leticia had never come up this way with me, she was too special for any kinda tricks.

Well, damn, maybe I should’ve brought her. But it’s not too late!

Follow me, I know a spot.

We walked down a big ramp into the shadowy grove where we could hear low chirps of birds and bugs and micos, buzzing together like a Pixinguinha samba. I could hear brusk quibbling not far off, and I knew those pesky germans had followed us. We walked until there was a clearing, looking over the hillside at the wide expanse of the Botafogo beach. The sun was dropping, coloring the few clouds in late day pinks and reds.

Rachel said, Woah, catching the view. Olivia was speechless.

I sat down on a rock and looked out over the abyss.

The city looked immense, and I was panged with pride by its enormity.

But we were loose up here, a deep drop if we slipped. Despite the thick trees and the natural hillside ledges, if you fell, you were probably fucked.

But then I saw something truly amazing. Perched there on the hillside, barely noticing our presence, was an enormous bird. With a bright red color and a huge curved beak.

Meu deus!

It flew off, wings beating against the air.

That’s an ibis, I didn’t know they could get this high, Mateus said.

Is that a good or bad sign?

I don’t know.

WHEN THE kid showed up, Rachel was taking pictures of Olivia. Me and Mateus were leaning against the rocks, chilling. I heard some rustling in the bamboo, and who else would it be but the german boy? Looking at us like it was no problem he was invading the private space we’d made with our presence, like it was no problem he was altering our whole environment. No, he belonged here. No family trailing him. Alone.

He climbed out to the area adjacent to us where the rocks jutted out, dangerous and unstable. Kid being teimoso, precarious as hell. It was late and everything was getting dark. A big tree that grew from the abyss hung over us, draped in shadows, its mute branches twisted around like ominous warnings.

We all stopped, just watched him, tense. As if a snake had snuck up on us. And then his family showed up. His mom walked to the edge of the bamboo and started scolding him, motioning him to rejoin them. But he wouldn’t even look at her.

I heard stirring from the dark tree.

I looked up and it was a mico! Against the blood red backdrop of the falling day, the sun crowning his head like a saint. Climbing out on the branch, chirping, squeaking, real cute.

I said, Look! And a gasp rose from the gathered group. The babaca father emerged carrying an H.Stern bag, but as soon as he saw the mico, he dropped the bag and pushed past his wife to get a picture.

The mico regal as the city on that high branch.

And then! sprouting like fruit from within the tree, six or seven of his subjects went to join their solitary king on the end of the branch, on the edge of the abyss. The whole court coming out to confront us like we had landed on their shores, unwelcome. They were nearest to the kid who was walking out closer and closer to the tree, closer to the abyss, close enough to where he could reach out and touch one.

The air around us congealed into a thick, hot tension. He swung his backpack around and started digging through it, his movements the focus of our collective gaze. With a nefarious look, he pulled out a banana. The banana glowing golden in the sunlight. Like a treasure for the micos. They stopped chirping and stared. We were silent. I wondered if maybe I had misjudged this kid, if he was about to offer some benefaction to the true residents of this mountain.

But no. He started waving the banana around taunting their attention, and then he fake threw it off the cliff as if he wanted the micos to jump for it and fall to their deaths. Those malandra micos didn’t budge. Instead, the kid lost his balance, stumbled, tried to catch himself, failed, and we all watched as he tumbled over the cliff, becoming a fading amplification of ahh!

Olivia screamed first, and then his mother.

The rest of us were just looking at eachother, jaws dropped aghast. And my stomach churned cold with nausea at the thought of another death weighing on me. The kid’s mom ran out, almost knocking down the foolish father who was catatonic with indecision. For a second, I thought she was gonna tumble off too and the rest of the family would follow until there was a pile of clumsy germans at the bottom of the cliff. But she held her ground and stood there yelling, Leo! frantic.

The moment hung in the air, all of us hoping hard he wasn’t dead.

The micos were looking down at us like, Yeah, but what about that banana?

The kid’s mom got down and crawled to the edge yelling his name like she could see him. And then he yelled back. Alive! and we could hear him crying. My worry subsided. He deserved it. A proper cosmic judgement for messing with those poor innocent micos. He got lucky. Very lucky. Usually when people fell off here it was a search and a half just to recover the body.

The girl and her mother were trying to communicate with the kid while the dad stood there and cried, the camera slung around his neck. I was kinda thinking, Pussy, maybe you deserve a dead kid. But I took the thought back.

It was getting darker and darker by the minute. And the police could sniff out a fallen turista, so I was a hundred percent ready to vambora. But I realized the girls were invested in this rescue. Mateus was with me, but Rachel was crouched with the mom trying to talk to the kid and Olivia was standing right behind her.

I said, Rachel. She looked over and I made a motion like, Let’s go!

She walked over.

He’s probably hurt. We have to help!

I’m not a fucking fireman, what am I gonna do?

She looked at me for a moment with those green eyes like maybe she noticed I wasn’t the guy she thought.

Yeah, you’re right. Let’s get help, Mateus! We’ll be right back.

She smiled and went to rejoin the bereaved.

We walked out of the grove and told some workers hanging around that a stupid german boy who was taunting the micos and being teimoso! had fallen off the cliff. The workers ran to get the firemen who hustled over worried frantic about a growing foreign body count that would surely clamp their wallets tighter. Neither of us were keen on the rescue, so we posted on a bench and lit up one of the joints that Mateus had brought with him. We sat there smoking and swatting away the initial mosquito assault. The lights and the bugs had woke around us, morning time for these nocturnal life cycles.

The weed was making me sad and silent. I was thinking about Leticia and my ruined future paths, veering toward despair. But then I reassured myself. Everything was gonna be cool. Anyway, this Rachel liked me. If the kid got saved and I played my cards right, I could get laid tonight. Mateus was playing guitar at a bar in Lapa. We could take them to see the show. I would teach Rachel some samba. Everything was gonna be fine. I just needed to get out of here and get a drink. Fast.

We heard a cheer rise up in the distance.

I killed the joint and stomped it out with my flipflop.

When we got back, the firemen were on the last stretch of their heaving rope pulley rescue. The air had changed, lightened. Relieved and hopeful was the mood. Rachel was chatting with the kid’s mom and when she saw us return, she gave me a big hug and said, Thank you so much for getting help! This family is so lovely. They’re from Belgium but they speak english.

Belgium! even worse.

Olivia was talking to the notdead kid’s sister. Their moronic patriarch was sitting on the ground staring blankly, as if he was some sort of victim. Maybe of a spoiled vacation.

The firemen yelled, Porra! and with one final haul the kid emerged over the edge, Young Lazurus on a stretcher. The emergency flood lights the firemen set up gave him a dead pale look. Apparently he hadn’t run out of tears because he was still crying. His leg looked fucked up and his clothes were covered with dirt and mud.

We all cheered.

The firemen picked up the stretcher like pallbearers and led our funeral procession out.

Rachel was walking next to me, and she reached out and held my hand.

We rearrived at the main area and I saw trouble. Two military police officers uniformed up, walking our way. An older one with a pastel swollen belly bursting out of his shirt, and a short dude about my age, with a walrus mustache. They stopped right in front of us. Smiling like leopards. The short one’s badge said Cunha, my name. The glutton was Grunewald and he took the lead, real polite.

Boa noite. What happened here?

A kid slipped and fell. He’s ok. You see him. I pointed over his way.

But what were you doing out there? I thought nobody was allowed?

I don’t know. I just followed the turistas.

Cunha took stock of Mateus. Looking him up and down. His old school Flamengo jersey. His bleached buzz cut and old flipflops.

Are these girls with you?

Yes. They’re americans.

He smiled and addressed them in english.

And then, as if he had a sixth sense for petty crime, he said, Can I see your tickets?

Rachel seemed calm. She said, We threw them away.

I said, Yeah, I thought we didn’t need em.

But Olivia, who was visibly nervous, goes, Someone snuck us up here!

Me and Mateus and Rachel all looked at her like fucking seriously?

The officers let that hang in the air.

You think that’s ok? Grunewald asked Mateus. You think it’s ok to do whatever you want? Tromp all over this country and go wherever you want without a care in the world?

Mateus said nothing and stared straight ahead, not looking at anything.

Cunha grabbed his face and forced him to make eye contact.

Attention moleque! He’s talking to you!

Look at his eyes, Grunewald said, He’s high!

Have you two been smoking weed?

I said no. Rachel who had been poised and composed started to fluster. Olivia was freaking out. Grunewald told Cunha to search Mateus. He shoved him to the ground, and sure enough, they found a bag with two joints in his pocket. Grunewald asked me, You got any on you? I said no but he turned me around and searched me. He didn’t find anything but when he was done he punched me in the stomach and said, Sorry. Cunha couldn’t help but laugh.

They started cuffing Mateus who was silent on the ground. I could feel his anger from here. They would keep Mateus overnight and it would take a bribe to get him out, a few hundred reals. Turistas with two joints would get off on the spot.

They stood him up and Olivia started to cry.

Rachel snapped at her, That’s not helping!

It’s gonna be ok, I said.

Cunha, who was walking behind Mateus, leading him, said, There’s only one more bondinho going down, if you want to get on it, you better move.

So we followed, silent, as the officers perp walked Mateus to the bondinho.

We boarded. The germans looked at us exhausted and confused. Grunewald made a smoking gesture and said, Drugs, in english. The useless father looked at us disappointed. His resurrected kid, who had finally stopped crying, was laying on a stretcher eating a popsicle.

We took the slow ride down the mountain together in the dark bondinho. The firemen and officers chatted about their respective heroism. Olivia was distraught. Rachel was worn out and clinging to me.

Suddenly Cunha said, Yes! Flamengo lost in extra time!

Mateus goes, This day keeps getting better.

I couldn’t help but laugh. He started laughing too.

Cala boca!

We all shut up.

We finally made it down and out the entrance. An ambulance was waiting there parked behind the police car, both their lights echoing off the dark empty air.

It was a hot ass night and there was nobody else hanging around the parking lot.

The germans and the firemen went left to the ambulance.

Our group went right to the cop car.

Sem problema cara, you’ll be out tomorrow.

Porra fudida, Mateus said, demure.

Olivia put her hand on the window in solidarity. Rachel had her arms wrapped around me. She was warm and smelled good.

The police left first and the ambulance followed. We were alone under a dim streetlight. The only sounds were the far off waves splashing and the bugs and night birds singing their sleepy songs. We stood in silence for a moment.

You guys tired?

Olivia said, I’m going home.

I’m not, Rachel said.

Do you wanna go out?

I could use a drink.

Olivia said, I’m going home.

Ok. Let’s head to the bus station.

No. I’ll call an uber.

BURUMBUM! I woke up grieved and troubled thunder shaking the room thin light peeking through the hotel curtain oh god dark snoring mass in the bed. Rachel. Burumbubum! heart beating fast. That nightmare woke me up quick. I hadn’t had a nightmare since I was a kid. Never had any dreams. But there I was, standing in the middle of Nossa Senhora getting hit with a terrible storm and the water rising higher and higher. I was knee deep in it, frozen, watching the building in front of me get wrecked by fire. The rain poured on the flames but the burning wouldn’t stop.

I could hear my grandma and Marta and Lucia screaming.

I knew they were burning up and I couldn’t save them.

And then I heard my mother’s laughter drowning out all the noise.

My heart was pounding like the thunder.

I shouldn’t be having any dreams. That was the point of blacking out! You sleep until the next morning, untroubled. I caught my breath and stood up. Shorts right there on the floor. Put them on. Walked over to the window, headache burgeoning. Rachel’s shit spilled about like a shipwreck. I peeked through the blinds. There was my slice of Copacabana.

Of course it was the Marriott. Where else would she be staying?

Burumbum! I was startled by the thunderclap and the lightning that flashed, cutting through the black ceiling of the sky. It looked like my dream. I might’ve screamed when the thunder hit because Rachel yelled groggy, It’s too early!

My phone was lying on the floor next to me. Dead.

Do you have a charger?

She didn’t say anything.

I realized she had an iPhone anyway so it wouldn’t do me any good. The room was a mess, like Rachel had a grudge against maids. My mom cleaned rooms at this hotel for a month. Until she was fired.

My head hurt so bad! I needed my shirt and my flops. I poked around for them and ended up finding a pile of twenty dollar bills. Eighty dollars. I stuffed it into my pocket. Something caught my attention on the wall, something written. I got closer and looked at it. It said Daniel and had my phone number written in permanent marker. Seems like something I would do. Except the number was way off. Which definitely seems like something I would do.

Be quiet and come back to bed.

Sorry.

I spotted my shirt on the floor. Damp and crusted in puke. Fuck. I was gonna have to get another shirt before I went to see Leticia. I guess I could go home. My grandma’s apartment was literally a block away. No. No. The last thing I wanted was a reunion. I was gonna have to slog through this rain shirtless. Porra!

But today was gonna be a good day!

I was gonna get Mateus out of jail.

And I was gonna get Leticia back.

Product Details

- Publisher: Washington Square Press (June 25, 2024)

- Length: 256 pages

- ISBN13: 9781668013885

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

"A bacchanal of familial entanglements, as beautiful as it is brutal. This is a story of what happens when love is the midwife of destruction, trauma the cousin of redemption, and fate, the absentee mother of us all. I loved this book in all its parts, but as a whole, it left me awestruck." —JAMIE FORD, New York Times bestselling author of The Many Daughters of Afong Moy

“With a tremendously powerful voice and a commanding hand, Harold Roger’s Tropicália shoots us out of a cannon from page one...With riveting and fearless prose and moments of tension so thick they make your spine tingle, Troplicália weaves us in and out of the Cunha family’s past and one inextricably linked week in their present that will force the siblings to decide if it's possible to escape fate and what it means to define ourselves on our own terms. This book and the humanity, humor and, yes, even rage, these characters made me feel, will stay with me for a long time." —XOCHITL GONZALEZ, New York Times bestselling author of Olga Dies Dreaming

“In these vibrant and hypnotizing pages, Harold has given us so much pain, grace, and love that when I finished reading I called my parents just to hear their voices.” —MICHAEL ZAPATA, author of The Lost Book of Adana Moreau

"One of the most marvelous books I've read in years...Intense, tender, and wise, and it reminds us that for each way that a family is split, it is also doubled; and that for each fury, there's a resplendent underside of love." —RIVKA GALCHEN, award-winning author of Atmospheric Disturbances

"A wild and moving saga, Tropicália bounds across generations and continents at a breakneck pace. With vivacious prose and an unflinching eye, Harold immerses readers in the cruel beauties of Rio de Janeiro and the cyclical traumas of a family who is learning to heal and forgive like any other, yet each in their own broken but hopeful way. Tropicália reminds us that forgiveness is possible but has to be earned—and before it's too late." —JAKOB GUANZON, author of Abundance

"Tropicália is a riotous search for catharsis and understanding. Harold captures the rage born out of family secrets and doesn't pull any punches. A powerful debut." —ZORAIDA CÓRDOVA, author of The Inheritance of Orquídea Divina

"A formally mesmerizing, ventriloquial, intergenerational epic about the difficulties of being born into a family. Harold's prose moves muscular and propulsive, somehow managing to stay radiating light and grace no matter how cruel the subject matter." —SEAN THOR CONROE, author of Fuccboi

“Rogers debuts with the riotous and tragicomic story of a Rio de Janeiro family in turmoil over lies, infidelity, and parental abandonment...Rogers’s plot sizzles as much as the Copacabana Beach where the party’s fateful events play out. This packs a powerful punch." —Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“Brazilian American Rogers’ debut novel is polyphonic, raw, and a revelation…Through that darkness, glimmers of love, hope, and redemption shine through Rogers’, by turns, shocking and brutal, effervescent and delightful tale....Young people will be moved by Daniel and Lucia’s plight, challenges, and choices.” — Booklist (starred review)

"[O]riginal and highly immersive" —Good Morning America

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Tropicália Trade Paperback 9781668013885

- Author Photo (jpg): Harold Rogers Used with the permission of Harold Rogers(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit