Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

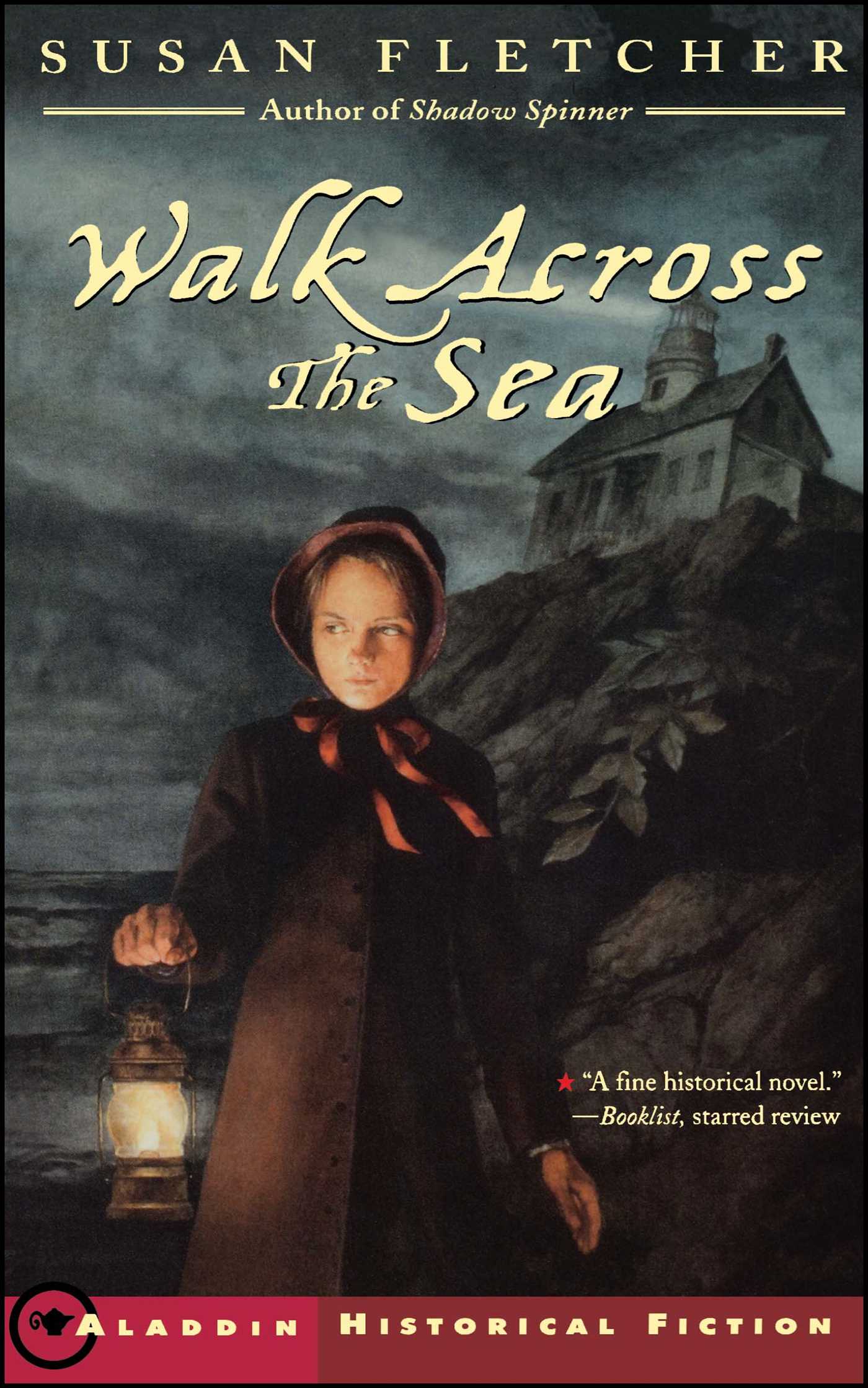

About The Book

The first time Eliza sees Wah Chung, he is squatting beside some rocks on the pathway to her island. Eliza's island is the one on which the lighthouse -- operated and maintained by her father -- stands, sending its beacon of safety to ships at sea. The pathway to the island is a treacherous one, engulfed by water when the tide is high, passable only when the tide is low and reveals the secret life of the sea on the rocks and in the pools that remain.

Although Eliza is careful to avoid Wah Chung as he paints among the rocks (after all, he is a Chinaman), when a "sneaker wave" approaches the passage, it is Wah Chung who warns her and then rescues Eliza's goat, Parthenia, before both are swept away.

It is a simple act of kindness, but one that causes Eliza to doubt many things. Are the Celestials, as the Chinese immigrants are called, such a threat to their small town? Are they really heathens, as her father claims? And what should she do when the townspeople conspire to expel these people forcibly? How will Eliza act, in the face of her father's strong beliefs and his duties as the lighthouse keeper, when Wah Chung comes to her for help in return?

Although Eliza is careful to avoid Wah Chung as he paints among the rocks (after all, he is a Chinaman), when a "sneaker wave" approaches the passage, it is Wah Chung who warns her and then rescues Eliza's goat, Parthenia, before both are swept away.

It is a simple act of kindness, but one that causes Eliza to doubt many things. Are the Celestials, as the Chinese immigrants are called, such a threat to their small town? Are they really heathens, as her father claims? And what should she do when the townspeople conspire to expel these people forcibly? How will Eliza act, in the face of her father's strong beliefs and his duties as the lighthouse keeper, when Wah Chung comes to her for help in return?

Excerpt

Chapter 1: The China Boy

March 1886

Crescent City, California

The beginning of the end of our life in the lighthouse was the day the goat got loose.

Well. There were many such days. Papa had bought her -- Parthenia -- to crop the poison oak and blackberry bushes that threatened to overtake our island. The milk was extra blessing.

Parthenia did her job too well. When she had taken her fill of brambles, she commenced upon Mama's vegetables and roses. Mama gave roses the go-by in time, but Papa built fence after fence for the garden before he finally set up one that goat looked upon as a discouragement.

After that, she raided other folks' gardens. She would escape the island at ebb tide, and after-ward we would hear reports -- Mrs. Somersby at church fuming about her hollyhocks, Horace Ahrens at school giving account of his mother's lost cabbages, Dr. Wilton from the hospital lamenting his late nasturtiums. Dr. Wilton was goodhearted about it though. He said Parthenia went tripping through the tiny clapboard hospital, entertaining the patients. The whole place felt jollier when she was there.

But Papa said it was not right to let Parthenia run loose. Besides, he said, the heathen Chinamen in the shanties at the edge of town were known to eat all manner of meat -- rat meat, crow meat, cat meat, dog meat. They'd likely look upon Parthenia as a tasty supper indeed. Still, that cantankerous goat would escape. She could gnaw through any rope. She could jump atop her shed and vault across the fence. She could lean against the slats and knock them flat. If she purely wanted out, we couldn't hold her -- just slow her down. It was my job to find her and fetch her home before the tide came in.

This day I'm telling of was a Saturday early in March -- two years ago, when I was thirteen. Parthenia had tucked into Mrs. Overmeyer's primroses, and that lady was none too pleased. "Eliza Jane McCully," she said when I came upon the scene, "you get that goat out of my garden, do you hear me? Shoo! Goat, shoo! Oh, my primroses! My poor, poor primroses!"

It took some doing to cultivate primroses so near the Pacific Ocean, with the constant salty wind and the sandy soil. Primroses -- and other flowers -- were a luxury and purely cherished by folks who grew them. I tied a rope around Parthenia's neck, and we played tug-o'-war for a spell, until she clapped eyes on the violets by the hospital and made a beeline in that direction. I managed to steer her away, toward the bluff above the isthmus. "Folks get contentious, with you laying into their flowers," I told her. "Haven't you noticed? Haven't you wondered why all the conniptions when you're about?"

Parthenia bleated mournfully, looked back at me with great, round, sorrowful eyes. She was misunderstood, she seemed to say. She was only hungry.

I first caught sight of Wah Chung when we reached the edge of the bluff. I didn't know yet he was called Wah Chung. I didn't know a blessed thing about him -- save that he was squatting beside some rocks on the path to our island, his long pigtail hanging down his back beneath a wide, flat straw hat. A Chinaman. Seemed like he was writing something. Or drawing, maybe.

I stood there a tick, not knowing what to do. I was forbidden to mill about the China shanties, as some children did, buying litchi nuts and ginger candies. "Heathen things," Papa called them. So I stayed away. I was forbidden even to speak to a Chinaman. "If you see one coming toward you," Papa said, "step away and don't look at him. If you meet their eyes, they might try to converse with you. Best have nothing to do with them."

But the tide was on the uprise that afternoon. It had already swallowed up most of the isthmus, and the thin, foamy edges of waves washed across the narrow way that remained. I couldn't get home without passing quite near to this Chinaman. And I dared not wait for him to leave.

If it hadn't been for Parthenia, I might have turned back. The Wiltons let me stay with them whenever it was needful -- when I became stranded on the mainland unexpectedly, or when, because of the tides, I had to leave for school early or turn homeward late. Mrs. Wilton had devised a signal to show that I was safely settled at their house: a yellow banner hung above their front porch and visible from the island. But the invitation did not include Parthenia. And besides, I didn't hanker for more doings with gardeners on a rampage.

I hurried along the steep path down the bluff. The brisk, sea-smelling wind whipped at my skirts and coat. It was a clear day, rare this time of year. High, thin clouds raced shoreward across a forever sky; gulls wheeled and cried overhead. Parthenia, at once seeming eager to be home, minced along before me, her udder bulging, flapping side to side. As we picked our way through the heaps of driftwood I saw the Chinaman glance toward us and away. He rose partway to his feet, seemed to think better of it, then squatted back on his heels and stared hard into the tide pool. It came to mind that he might wish to be shut of me as fervently as I wished to avoid him. But I had cut off his avenue of retreat.

Drawing near, I saw that he was holding a paintbrush and a sheet of paper tacked to a board. An ink jar sat on a rock beside him. A wave lapped over his bare feet and wet the legs of his baggy denim trousers, but he did not try to escape it by moving into our path. He sat like a stone. When we had nearly come abreast, Parthenia gave a quick, hard lurch in the Chinaman's direction

and tried to bite his hat. I yanked her away and stepped sideways into a tide pool, flooding my boots with cold water, soaking my skirt and petticoat to my knees. A jet of anger spurted up inside me. This was our path to our island. What business had he here?

He did not look up. I cinched Parthenia's rope, clambered out of the pool and, shoes sloshing in my boots, marched for home.

But now Parthenia dawdled. She kept craning back to ogle the Chinaman, no doubt lusting after his hat. I slapped her flanks to urge her along -- a mistake, I discovered. She balked -- head down, ears back, legs splayed. "Come along, Parthenia," I said between clenched teeth. For pure cussedness that goat could not be beat. She backed toward the mainland, glaring at me. I jerked her rope sharp -- another mistake. She wheeled round and bolted toward the Chinaman so quick, she took me off guard. Her rope slipped, burning, through my hand. I snatched at it, missed, and stumbled forward, hoping to catch hold of goat or rope before she reached the Chinaman.

He had turned to stare. His eyes looked wild. He leaped to his feet, flailed his arms, shouted something I couldn't understand. My heart stopped. Was he threatening me? Trying to scare me away from Parthenia so he could steal her? But something about the way he moved made me look over my shoulder, and then I saw it -- a wave, a great, tall breaker, looming behind me. I ran, tripped, fell -- my skirts were heavy, clinging. I got up and scrambled across a heap of rocks to a sturdy-looking boulder, then clung to the landward side as Papa had taught me -- crouching, nestling into the curves of it, digging my fingers into its crannies. And the wave came roar-ing down upon me. Green water -- not just white water and foam. It poured over my head, engulfed me to my waist, knocked me about, tried to jerk my feet from under me and pry me away. I pressed against the boulder until barnacles cut into my skin. The current dragged at me, so strong. My fingers slipped; I was peeling away...

Then it was past. I dashed the stinging salt spray from my eyes and scanned the sea. Though water still sucked at my skirts below my knees, I saw nothing alarming on the horizon.

A sneaker wave. I had been caught by them before, though never so direly as this, and Papa warned me constantly against them. Never turn your back on the sea, he always said -- though of course we must, at times. But it was folly to do so for long.

And now I heard a piteous bleat. Parthenia! I turned to see her flailing in the arms of the Chinaman. I had a mind to shout at him, to tell him to put her down, but then I saw that he was wading toward me. "You...goat," he said. He set her down in the ebbing water and held out the end of the rope to me. He was drenched, head to foot. Hat gone, long blue jacket torn, a fresh gash across one cheek. He stood just my height, I saw. He seemed...my age, or very near.

A China boy.

Parthenia bleated again, long and deep and sad. She was a sorry sight, all stomach, bones, and udder, with her hair plastered to her body, and her slotted amber eyes reproaching me. All at once I felt ashamed. I had not given her a thought, had just run to save my own skin. And yet this China boy...Had he rescued Parthenia from the wave? Or just plucked her up after it had passed?

He held out the rope again. "You...goat," he said.

I glanced over my shoulder at the sea -- all was well -- then hastened toward the China boy. I kept my eyes averted. But at the last moment, when I was about to mumble my thanks, my eyes snagged on his -- strange, lidless-seeming, almond-shaped. Something moved inside me, like a sudden shift in the wind.

The China boy ducked his head. I snatched the rope from his hand.

"Come along, Parthenia," I said sternly. "Come along!"

Copyright © 2001 by Susan Fletcher

March 1886

Crescent City, California

The beginning of the end of our life in the lighthouse was the day the goat got loose.

Well. There were many such days. Papa had bought her -- Parthenia -- to crop the poison oak and blackberry bushes that threatened to overtake our island. The milk was extra blessing.

Parthenia did her job too well. When she had taken her fill of brambles, she commenced upon Mama's vegetables and roses. Mama gave roses the go-by in time, but Papa built fence after fence for the garden before he finally set up one that goat looked upon as a discouragement.

After that, she raided other folks' gardens. She would escape the island at ebb tide, and after-ward we would hear reports -- Mrs. Somersby at church fuming about her hollyhocks, Horace Ahrens at school giving account of his mother's lost cabbages, Dr. Wilton from the hospital lamenting his late nasturtiums. Dr. Wilton was goodhearted about it though. He said Parthenia went tripping through the tiny clapboard hospital, entertaining the patients. The whole place felt jollier when she was there.

But Papa said it was not right to let Parthenia run loose. Besides, he said, the heathen Chinamen in the shanties at the edge of town were known to eat all manner of meat -- rat meat, crow meat, cat meat, dog meat. They'd likely look upon Parthenia as a tasty supper indeed. Still, that cantankerous goat would escape. She could gnaw through any rope. She could jump atop her shed and vault across the fence. She could lean against the slats and knock them flat. If she purely wanted out, we couldn't hold her -- just slow her down. It was my job to find her and fetch her home before the tide came in.

This day I'm telling of was a Saturday early in March -- two years ago, when I was thirteen. Parthenia had tucked into Mrs. Overmeyer's primroses, and that lady was none too pleased. "Eliza Jane McCully," she said when I came upon the scene, "you get that goat out of my garden, do you hear me? Shoo! Goat, shoo! Oh, my primroses! My poor, poor primroses!"

It took some doing to cultivate primroses so near the Pacific Ocean, with the constant salty wind and the sandy soil. Primroses -- and other flowers -- were a luxury and purely cherished by folks who grew them. I tied a rope around Parthenia's neck, and we played tug-o'-war for a spell, until she clapped eyes on the violets by the hospital and made a beeline in that direction. I managed to steer her away, toward the bluff above the isthmus. "Folks get contentious, with you laying into their flowers," I told her. "Haven't you noticed? Haven't you wondered why all the conniptions when you're about?"

Parthenia bleated mournfully, looked back at me with great, round, sorrowful eyes. She was misunderstood, she seemed to say. She was only hungry.

I first caught sight of Wah Chung when we reached the edge of the bluff. I didn't know yet he was called Wah Chung. I didn't know a blessed thing about him -- save that he was squatting beside some rocks on the path to our island, his long pigtail hanging down his back beneath a wide, flat straw hat. A Chinaman. Seemed like he was writing something. Or drawing, maybe.

I stood there a tick, not knowing what to do. I was forbidden to mill about the China shanties, as some children did, buying litchi nuts and ginger candies. "Heathen things," Papa called them. So I stayed away. I was forbidden even to speak to a Chinaman. "If you see one coming toward you," Papa said, "step away and don't look at him. If you meet their eyes, they might try to converse with you. Best have nothing to do with them."

But the tide was on the uprise that afternoon. It had already swallowed up most of the isthmus, and the thin, foamy edges of waves washed across the narrow way that remained. I couldn't get home without passing quite near to this Chinaman. And I dared not wait for him to leave.

If it hadn't been for Parthenia, I might have turned back. The Wiltons let me stay with them whenever it was needful -- when I became stranded on the mainland unexpectedly, or when, because of the tides, I had to leave for school early or turn homeward late. Mrs. Wilton had devised a signal to show that I was safely settled at their house: a yellow banner hung above their front porch and visible from the island. But the invitation did not include Parthenia. And besides, I didn't hanker for more doings with gardeners on a rampage.

I hurried along the steep path down the bluff. The brisk, sea-smelling wind whipped at my skirts and coat. It was a clear day, rare this time of year. High, thin clouds raced shoreward across a forever sky; gulls wheeled and cried overhead. Parthenia, at once seeming eager to be home, minced along before me, her udder bulging, flapping side to side. As we picked our way through the heaps of driftwood I saw the Chinaman glance toward us and away. He rose partway to his feet, seemed to think better of it, then squatted back on his heels and stared hard into the tide pool. It came to mind that he might wish to be shut of me as fervently as I wished to avoid him. But I had cut off his avenue of retreat.

Drawing near, I saw that he was holding a paintbrush and a sheet of paper tacked to a board. An ink jar sat on a rock beside him. A wave lapped over his bare feet and wet the legs of his baggy denim trousers, but he did not try to escape it by moving into our path. He sat like a stone. When we had nearly come abreast, Parthenia gave a quick, hard lurch in the Chinaman's direction

and tried to bite his hat. I yanked her away and stepped sideways into a tide pool, flooding my boots with cold water, soaking my skirt and petticoat to my knees. A jet of anger spurted up inside me. This was our path to our island. What business had he here?

He did not look up. I cinched Parthenia's rope, clambered out of the pool and, shoes sloshing in my boots, marched for home.

But now Parthenia dawdled. She kept craning back to ogle the Chinaman, no doubt lusting after his hat. I slapped her flanks to urge her along -- a mistake, I discovered. She balked -- head down, ears back, legs splayed. "Come along, Parthenia," I said between clenched teeth. For pure cussedness that goat could not be beat. She backed toward the mainland, glaring at me. I jerked her rope sharp -- another mistake. She wheeled round and bolted toward the Chinaman so quick, she took me off guard. Her rope slipped, burning, through my hand. I snatched at it, missed, and stumbled forward, hoping to catch hold of goat or rope before she reached the Chinaman.

He had turned to stare. His eyes looked wild. He leaped to his feet, flailed his arms, shouted something I couldn't understand. My heart stopped. Was he threatening me? Trying to scare me away from Parthenia so he could steal her? But something about the way he moved made me look over my shoulder, and then I saw it -- a wave, a great, tall breaker, looming behind me. I ran, tripped, fell -- my skirts were heavy, clinging. I got up and scrambled across a heap of rocks to a sturdy-looking boulder, then clung to the landward side as Papa had taught me -- crouching, nestling into the curves of it, digging my fingers into its crannies. And the wave came roar-ing down upon me. Green water -- not just white water and foam. It poured over my head, engulfed me to my waist, knocked me about, tried to jerk my feet from under me and pry me away. I pressed against the boulder until barnacles cut into my skin. The current dragged at me, so strong. My fingers slipped; I was peeling away...

Then it was past. I dashed the stinging salt spray from my eyes and scanned the sea. Though water still sucked at my skirts below my knees, I saw nothing alarming on the horizon.

A sneaker wave. I had been caught by them before, though never so direly as this, and Papa warned me constantly against them. Never turn your back on the sea, he always said -- though of course we must, at times. But it was folly to do so for long.

And now I heard a piteous bleat. Parthenia! I turned to see her flailing in the arms of the Chinaman. I had a mind to shout at him, to tell him to put her down, but then I saw that he was wading toward me. "You...goat," he said. He set her down in the ebbing water and held out the end of the rope to me. He was drenched, head to foot. Hat gone, long blue jacket torn, a fresh gash across one cheek. He stood just my height, I saw. He seemed...my age, or very near.

A China boy.

Parthenia bleated again, long and deep and sad. She was a sorry sight, all stomach, bones, and udder, with her hair plastered to her body, and her slotted amber eyes reproaching me. All at once I felt ashamed. I had not given her a thought, had just run to save my own skin. And yet this China boy...Had he rescued Parthenia from the wave? Or just plucked her up after it had passed?

He held out the rope again. "You...goat," he said.

I glanced over my shoulder at the sea -- all was well -- then hastened toward the China boy. I kept my eyes averted. But at the last moment, when I was about to mumble my thanks, my eyes snagged on his -- strange, lidless-seeming, almond-shaped. Something moved inside me, like a sudden shift in the wind.

The China boy ducked his head. I snatched the rope from his hand.

"Come along, Parthenia," I said sternly. "Come along!"

Copyright © 2001 by Susan Fletcher

Product Details

- Publisher: Margaret K. McElderry Books (October 18, 2011)

- Length: 224 pages

- ISBN13: 9781439132395

- Ages: 10 - 14

Browse Related Books

Awards and Honors

- Children's Literature Choice List

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Walk Across the Sea eBook 9781439132395

- Author Photo (jpg): Susan Fletcher Photo by Robby Lozano, Ten23 Photography(0.1 MB)

Any use of an author photo must include its respective photo credit