Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Witches, Druids, and Sin Eaters

The Common Magic of the Cunning Folk of the Welsh Marches

With Sophie Gallagher

Published by Destiny Books

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

Table of Contents

About The Book

A guide to ancient beliefs including instructions for magic and spellcasting

• Describes the arcane rituals, ancient beliefs, and secret rites of the Welsh Marches, including those of the Sin Eaters, Eye Biters, and Spirit Hunters

• Shares extracts from ancient texts stored in the archives of the National Museum of Wales, along with many original photographs of related artifacts

• Includes a Grimoire of the Welsh Marches, a wide collection of spells and magical workings along with practical instruction on crafting and casting

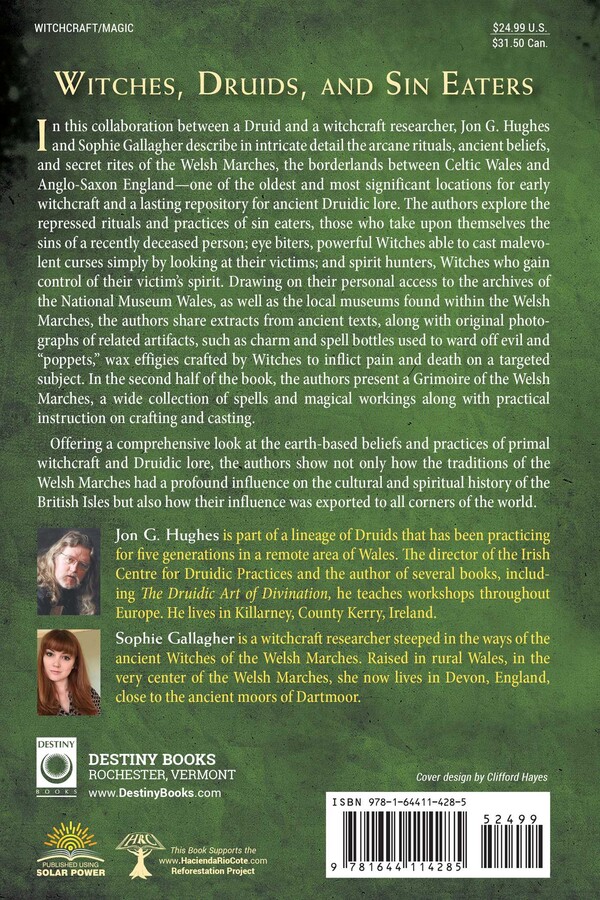

In this collaboration between a Druid and a witchcraft researcher, Jon G. Hughes and Sophie Gallagher describe in intricate detail the arcane rituals, ancient beliefs, and secret rites of the Welsh Marches, the borderlands between Celtic Wales and Anglo-Saxon England--one of the oldest and most significant locations for early witchcraft and a lasting repository for ancient Druidic lore. The authors explore the repressed rituals and practices of sin eaters, those who take upon themselves the sins of a recently deceased person; eye biters, powerful Witches able to cast malevolent curses simply by looking at their victims; and spirit hunters, Witches who gain control of their victim’s spirit. Drawing on their personal access to the archives of the National Museum Wales, as well as the local museums found within the Welsh Marches, the authors share extracts from ancient texts, along with original photographs of related artifacts, such as charm and spell bottles used to ward off evil and “poppets,” wax effigies crafted by Witches to inflict pain and death on a targeted subject. In the second half of the book, the authors present a Grimoire of the Welsh Marches, a wide collection of spells and magical workings along with practical instruction on crafting and casting.

Offering a comprehensive look at the earth-based beliefs and practices of primal witchcraft and Druidic lore, the authors show not only how the traditions of the Welsh Marches had a profound influence on the cultural and spiritual history of the British Isles but also how their influence was exported to all corners of the world.

• Describes the arcane rituals, ancient beliefs, and secret rites of the Welsh Marches, including those of the Sin Eaters, Eye Biters, and Spirit Hunters

• Shares extracts from ancient texts stored in the archives of the National Museum of Wales, along with many original photographs of related artifacts

• Includes a Grimoire of the Welsh Marches, a wide collection of spells and magical workings along with practical instruction on crafting and casting

In this collaboration between a Druid and a witchcraft researcher, Jon G. Hughes and Sophie Gallagher describe in intricate detail the arcane rituals, ancient beliefs, and secret rites of the Welsh Marches, the borderlands between Celtic Wales and Anglo-Saxon England--one of the oldest and most significant locations for early witchcraft and a lasting repository for ancient Druidic lore. The authors explore the repressed rituals and practices of sin eaters, those who take upon themselves the sins of a recently deceased person; eye biters, powerful Witches able to cast malevolent curses simply by looking at their victims; and spirit hunters, Witches who gain control of their victim’s spirit. Drawing on their personal access to the archives of the National Museum Wales, as well as the local museums found within the Welsh Marches, the authors share extracts from ancient texts, along with original photographs of related artifacts, such as charm and spell bottles used to ward off evil and “poppets,” wax effigies crafted by Witches to inflict pain and death on a targeted subject. In the second half of the book, the authors present a Grimoire of the Welsh Marches, a wide collection of spells and magical workings along with practical instruction on crafting and casting.

Offering a comprehensive look at the earth-based beliefs and practices of primal witchcraft and Druidic lore, the authors show not only how the traditions of the Welsh Marches had a profound influence on the cultural and spiritual history of the British Isles but also how their influence was exported to all corners of the world.

Excerpt

From Chapter 1: A Curious Beginning

In the depths of a very cold October in 2019, I received a call from an old friend of mine who lives near the market town of Shrewsbury, on the borders of Wales and England. He is very fortunate in having recently inherited an old farmhouse in a beautiful rural area of Shropshire and rang me because he knows well of my involvement in the Druidic community and my interest in all matters occult.

I was intrigued to hear that during the recent refurbishments at his farmhouse he had discovered a strange collection of items that had been found plastered into a void behind a mantlepiece above an old fireplace in one of the downstairs rooms of the house. The small cache contained what he called a medallion, a piece of charred paper that was completely blackened with nothing apparently written on it, and a bundle of small bent pins, tied together with thin thread.

I am sure he knew before he rang that his unexpected find would pique my interest, and he was, of course, quite right. Although none of these peculiar objects made me think of anything Druidic, hidden items like those he described certainly have a place in the broader occult practices to be found in both England and Wales in days gone by.

Understandably, in light of the age of his farmhouse, he was interested to discover if his find had any significant financial value, but as he continued to describe the items in more detail, it became obvious that the greatest value that could be attributed to his find would be in relation to its cultural significance. I suggested he show his find to members of the local archaeological societies or the regional museum, as having lived in the town of Shrewsbury for a short time, I knew that both organizations were very active and had an enthusiastic following. With an audible sigh, he told me that he had already contacted both those organizations and had been told much the same, namely that while the items were locally interesting, they had no particular financial value and therefore maybe he should hang on to them as family mementos and as interesting talking pieces for his visitors.

All the same, I asked him to send me copies of photographs of his find, as I was still very interested in seeing them for myself. He said he would do better than that, and having sent the initial pictures, he packed all the items into a padded envelope and posted them directly to me. When the package arrived a few days later, I carefully unpacked the three small boxes, each containing one of the newly discovered artifacts. It was obvious from the outset that the items had been combined to create an apotropaic device, a collection of meaningful occult items intended to protect the farmhouse and its occupants from malevolent forces and influences. These types of protective tokens were not unusual in the Welsh Marches, along the border of England and Wales, around the time that the farmhouse had been built. There were, however, two very unusual aspects to the find: the first was the intended power and potency of the combined artifacts, suggesting a dire need for powerful protection against some now-unknown threat; the second was that within the small collection of artifacts were items and images that are representative of two, normally separate, occult traditions, one being that of ancient witchcraft and the other, the lore of the Druidic tradition, both combined in a way that has never been witnessed previously.

Before proceeding any further with my exploration, I decided to consult two other, well-known information sources, the first an experienced and knowledgeable Witch, steeped in the tradition of the Welsh Marches, and the second the curators of the archives of the National Museum Wales, where I knew there was a rich source of relevant artifacts and contemporary texts and manuscripts. The National Museum in turn connected me to a network of regional and local museums and societies where I was later to find a wealth of exciting and eye-opening facts. Having done this and established my research resources, I invited my colleague, the aforementioned Witch researcher, to join me in my journey of exploration and become my coauthor in this eventual book. And so the stage was set and our detailed work could begin, but first an initial meeting to examine in detail the items from the find and to plan our research methodology and a timetable to proceed.

In the meantime, I returned the artifacts to their original owner, asking him at the same time to look at the walls and woodwork surrounding all the entrances to the house to see if he could find any other marks of hidden deposits that seemed out of place and if he were to find any, to let me know immediately.

Around two weeks later, I received another mysterious package from Shropshire. Inside I discovered fragments of birch bark and a short length of thorn branch, two more artifacts that, found secreted behind a lintel above a doorframe, were undoubtedly concealed protective devices, put there with the intention of warding off Witches and their familiars.

The fragments of silver birch bark were undoubtedly the dried and shriveled parts of a silver birch bark parchment curse that had separated into thin, dried-out strips. Though there was no visible script remaining on the fragments, there were faint traces of red markings, either text or drawings long since faded. There is a well-known tradition of Witches’ (and Druids’) curses being written on small squares of silver birch bark, a practice that gave the silver birch tree the country name of paper birch, and the small sheets of white bark used as paper being called scholar’s parchment (Welsh: memrwn ysgolhaig) in the Druidic tradition.

The short length of thorn branch was another common protective device hidden around the entrances of homes with the intention of warding off evil daemons and Witches. The sharp thorns from all sorts of thorny bushes and trees were thought to deter Witches, as they reputedly feared all sharp objects. On occasions, all the thorns but one were removed from a thorny twig, which then became a small pick known as a witch axe, which was used in the same way to warn away Witches and daemons. At other times, the individual thorns were removed from the branch and scattered on mantles or windowsills or even included in witch bottles with the same intention.

These latest artifacts served to further intensify our curiosity, and we began to finalize our plans to visit the various sites we had identified and begin our research in earnest. Our first efforts were to decode the amulet and interpret the sigils that formed the protective power it emanated.

In the depths of a very cold October in 2019, I received a call from an old friend of mine who lives near the market town of Shrewsbury, on the borders of Wales and England. He is very fortunate in having recently inherited an old farmhouse in a beautiful rural area of Shropshire and rang me because he knows well of my involvement in the Druidic community and my interest in all matters occult.

I was intrigued to hear that during the recent refurbishments at his farmhouse he had discovered a strange collection of items that had been found plastered into a void behind a mantlepiece above an old fireplace in one of the downstairs rooms of the house. The small cache contained what he called a medallion, a piece of charred paper that was completely blackened with nothing apparently written on it, and a bundle of small bent pins, tied together with thin thread.

I am sure he knew before he rang that his unexpected find would pique my interest, and he was, of course, quite right. Although none of these peculiar objects made me think of anything Druidic, hidden items like those he described certainly have a place in the broader occult practices to be found in both England and Wales in days gone by.

Understandably, in light of the age of his farmhouse, he was interested to discover if his find had any significant financial value, but as he continued to describe the items in more detail, it became obvious that the greatest value that could be attributed to his find would be in relation to its cultural significance. I suggested he show his find to members of the local archaeological societies or the regional museum, as having lived in the town of Shrewsbury for a short time, I knew that both organizations were very active and had an enthusiastic following. With an audible sigh, he told me that he had already contacted both those organizations and had been told much the same, namely that while the items were locally interesting, they had no particular financial value and therefore maybe he should hang on to them as family mementos and as interesting talking pieces for his visitors.

All the same, I asked him to send me copies of photographs of his find, as I was still very interested in seeing them for myself. He said he would do better than that, and having sent the initial pictures, he packed all the items into a padded envelope and posted them directly to me. When the package arrived a few days later, I carefully unpacked the three small boxes, each containing one of the newly discovered artifacts. It was obvious from the outset that the items had been combined to create an apotropaic device, a collection of meaningful occult items intended to protect the farmhouse and its occupants from malevolent forces and influences. These types of protective tokens were not unusual in the Welsh Marches, along the border of England and Wales, around the time that the farmhouse had been built. There were, however, two very unusual aspects to the find: the first was the intended power and potency of the combined artifacts, suggesting a dire need for powerful protection against some now-unknown threat; the second was that within the small collection of artifacts were items and images that are representative of two, normally separate, occult traditions, one being that of ancient witchcraft and the other, the lore of the Druidic tradition, both combined in a way that has never been witnessed previously.

Before proceeding any further with my exploration, I decided to consult two other, well-known information sources, the first an experienced and knowledgeable Witch, steeped in the tradition of the Welsh Marches, and the second the curators of the archives of the National Museum Wales, where I knew there was a rich source of relevant artifacts and contemporary texts and manuscripts. The National Museum in turn connected me to a network of regional and local museums and societies where I was later to find a wealth of exciting and eye-opening facts. Having done this and established my research resources, I invited my colleague, the aforementioned Witch researcher, to join me in my journey of exploration and become my coauthor in this eventual book. And so the stage was set and our detailed work could begin, but first an initial meeting to examine in detail the items from the find and to plan our research methodology and a timetable to proceed.

In the meantime, I returned the artifacts to their original owner, asking him at the same time to look at the walls and woodwork surrounding all the entrances to the house to see if he could find any other marks of hidden deposits that seemed out of place and if he were to find any, to let me know immediately.

Around two weeks later, I received another mysterious package from Shropshire. Inside I discovered fragments of birch bark and a short length of thorn branch, two more artifacts that, found secreted behind a lintel above a doorframe, were undoubtedly concealed protective devices, put there with the intention of warding off Witches and their familiars.

The fragments of silver birch bark were undoubtedly the dried and shriveled parts of a silver birch bark parchment curse that had separated into thin, dried-out strips. Though there was no visible script remaining on the fragments, there were faint traces of red markings, either text or drawings long since faded. There is a well-known tradition of Witches’ (and Druids’) curses being written on small squares of silver birch bark, a practice that gave the silver birch tree the country name of paper birch, and the small sheets of white bark used as paper being called scholar’s parchment (Welsh: memrwn ysgolhaig) in the Druidic tradition.

The short length of thorn branch was another common protective device hidden around the entrances of homes with the intention of warding off evil daemons and Witches. The sharp thorns from all sorts of thorny bushes and trees were thought to deter Witches, as they reputedly feared all sharp objects. On occasions, all the thorns but one were removed from a thorny twig, which then became a small pick known as a witch axe, which was used in the same way to warn away Witches and daemons. At other times, the individual thorns were removed from the branch and scattered on mantles or windowsills or even included in witch bottles with the same intention.

These latest artifacts served to further intensify our curiosity, and we began to finalize our plans to visit the various sites we had identified and begin our research in earnest. Our first efforts were to decode the amulet and interpret the sigils that formed the protective power it emanated.

Product Details

- Publisher: Destiny Books (September 20, 2022)

- Length: 312 pages

- ISBN13: 9781644114285

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Witches, Druids, and Sin Eaters Trade Paperback 9781644114285