Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

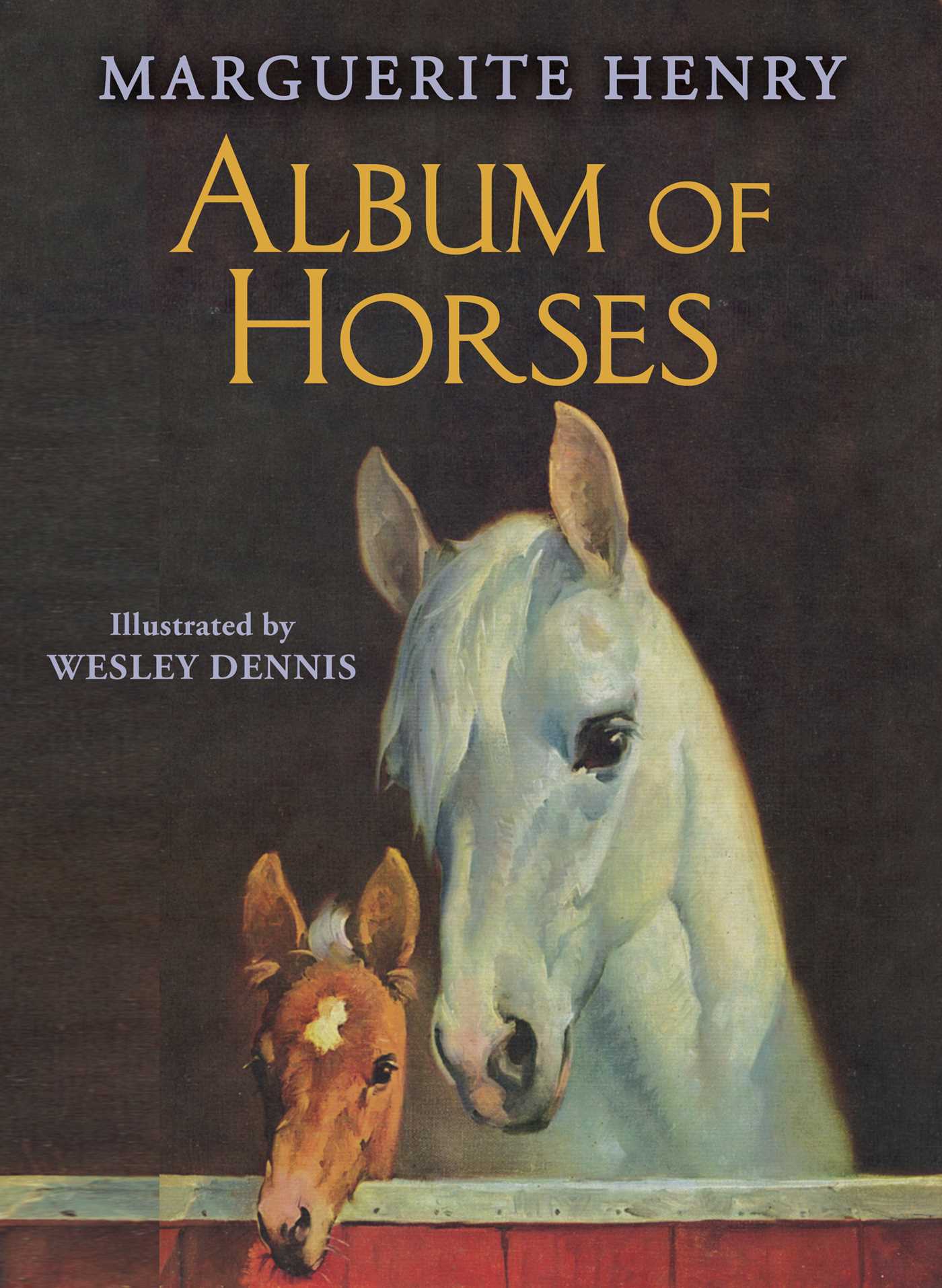

From award-winning author Marguerite Henry comes a classic reference work about horses and their origins.

How did the Morgan horse get its name?

What are the differences between a Belgian and a Clydesdale?

Why are the Byerly Turk, Darley Arabian, and Godolphin Arabian so important?

Find the answers to these and many other intriguing questions in Marguerite Henry’s Album of Horses. The award-winning author of Misty of Chincoteague and King of the Wind describes in vivid detail the hardworking Shire, the elegant Lipizzan, the spirited Mustang, and many more.

Each description is paired with a full color illustration by Wesley Dennis. This keepsake edition is a gorgeous addition to any collection of Henry’s books and a favorite for years to come!

How did the Morgan horse get its name?

What are the differences between a Belgian and a Clydesdale?

Why are the Byerly Turk, Darley Arabian, and Godolphin Arabian so important?

Find the answers to these and many other intriguing questions in Marguerite Henry’s Album of Horses. The award-winning author of Misty of Chincoteague and King of the Wind describes in vivid detail the hardworking Shire, the elegant Lipizzan, the spirited Mustang, and many more.

Each description is paired with a full color illustration by Wesley Dennis. This keepsake edition is a gorgeous addition to any collection of Henry’s books and a favorite for years to come!

Excerpt

Album of Horses

THE ARAB

SUN SCORCHING THE DESERT, WITHERING bushes and spears of grass. Sun beating down on the camel train, parching the lips of riders, slowing thoughts, slowing camel feet, slowing all living things of the desert except—except the small, delicate mares capering alongside the caravan.

Silently the cavalcade moves beneath the fierceness of the sun until out of nowhere a cry tears the desert stillness. Sand clouds whirl and hulk along the horizon. An enemy tribe! As one, the riders leap from their camels onto the backs of the mares and gallop toward the enemy, white robes billowing, lances gleaming in the sun.

Now steel meets steel and the mares are no longer playful. They are whirling dervishes—spinning on their hocks, charging, rushing ahead, missing a flying lance, wheeling, stopping, starting, galloping until lungs are fit to burst.

This is tribal warfare. This is Arabia from the ancient days until the time when the deadly lance almost wiped out the fiery little steed.

Always the desert warrior preferred to ride a mare to battle. Banat er Rih he called her, which in Arabic means “Daughter of the Wind.” And that is how she traveled—a quick gust when the enemy pursued, a steady pace when no one threatened. Endless miles today and tomorrow and the day after tomorrow. And all of this she could endure on the scantiest fare, on dry herbage and bruised dates, and even dead locusts when there were no grasses.

But no matter how meager the fare, her master saw that her thirst was quenched. On the march he carried an animal hide to make into a water vessel especially for her, and at night he milked his camel and gave the fresh, foaming milk to the mare before he fed his family. She was one of his own tentfolk, eating what they ate, dozing when they dozed. Children sometimes slept between her feet, their heads pillowed on her belly.

It is doubtful if the desert men loved their horses as pets. Rather, they depended on them to warn, with loud neighings, of the enemy’s approach, to carry them swiftly and safely in battle. And so a good mare was almost never for sale. She was better than gold or silver in the purse. She was wealth, freedom, and power. She was life itself. To sell her was unworthy; to give her away, a princely act.

An Arab chieftain jealously guarded his mare’s reputation for swiftness. And he bred her to only the noblest of stallions so that the pedigree of the foal became sacred. Often it was inscribed on parchment and tied in a little bag around the foal’s neck, with a few azure beads to keep away evil spirits.

When a foal was several months old, it was given a camel as nurse-mare. The big clumsy creature adopted the nimble little one wholeheartedly, screaming in worried tones if it strayed, snorting softly when it came near. She refused to move from camp unless the foal accompanied her.

It was common practice to take these foals along on the march, letting them frisk beside their sedate stepmammas. Sometimes during the monotonous journey a young Bedouin boy would spring lightly onto a colt’s back, clinging stoutly with naked legs. As simply as that, first training began. Later, as a three-year-old, the colt would be taught the movements of galloping in figure eights, changing leads at every turn, halting in mid-career, and all this was accomplished without punishment of any kind. Horsemen of the desert were patient. They had Time.

To judge the qualities of an Arab horse, the desert men would study the head first. Were the eyes like those of the antelope, set low and wide apart? Enormous and dark in repose? Fiery as sun and stars in excitement? And the ears—did they prick and point inward as if each point were a magnet for the other? And was the face wedge-shaped? Wide at the forehead, tapering to a muzzle so fine the creature might lip water from a tea cup? And did the profile hollow out between forehead and muzzle like the surface of a saucer? If all the answers were yes, the animal was of royal blood.

Color was of no great concern. Chestnut or bay, nutmeg brown or iron gray, all were good. But, under the hair, the skin had to be jet black for protection against the rays of the sun. This underlying blackness is still found in Arabians today and it gives to the bodycoat a lively luster.

As for size, even the smallest Arabians are big enough. Warriors of all eras rode them to battle. George Washington’s Arabian charger, Magnolia, was delicately made, but she was big enough to carry him through his fiercest campaigns. And Napoleon’s desert stallion, Marengo, bore him on his long retreat from Moscow.

What were the beginnings of these little warriors? Where did they come from? Did the Creator actually take a handful of south wind and say, “I create thee, O Arabian; I give thee flight without wings”?

Storytellers of Arabia explain it this way. “Since time’s beginning,” they say, “the root or spring of the horse was in the land of the Arab. Our sheiks found them running wild. They caught the foals and gentled them.” History can discover no better answer. The Arab horse is the oldest domesticated species in the world. Early rock drawings depict slender horses with arched necks and the typical high-flung tails, for all the world like today’s Arabs.

The storytellers relate that the Prophet Mohammed would tolerate only the most obedient mares for his campaigns. To test them he penned a hundred thirst-maddened horses within sight and smell of a clear stream. Turned loose at last, they stampeded for water but, almost there, they heard the notes of the war bugle. Only five mares halted. These were chosen by the Prophet to mother the race.

One of the five was named “Of-the-Cloak” because of a curious incident. A rider, escaping from an enemy, threw off his cloak for greater freedom. Picture his surprise when he arrived in camp to find that the arched tail of his mare had caught and held the cloak. Ever afterward this mare’s descendants were called Abeyan or “Of-the-Cloak.” Today the up-flung tail of the Arab is one of the chief characteristics of the species.

When recent wars threatened the Arabian horse with extinction, Sir Wilfred Blunt and his wife, Lady Anne, imported the finest Arab mares and stallions into England. They knew that Arab blood is a white flame in its purity and, if it were snuffed out, there would be no way to refresh the blood of modern breeds. Today America is helping in the crusade which the Blunts began. There are now more Arabian horses in the United States than in all Arabia! They are used for pleasure and for work on ranches. But these uses are of small importance. Wise horsemen are carrying on the strain, breeding Arabian stallions to Arabian mares to preserve the blood in its purity. Then it will always be available for future generations. Arabian blood is like the rare elements added to steel which give it the superior qualities of fineness and strength.

And so the blood of the “Daughters of the Wind” has streamed west, its strength undiluted, its character unchanged. In the wide-set eyes of these Arabian horses there is still the fire of sun and stars, and in their motion the flow of small winds and the tide of great ones. War horses. Builders of other breeds. Yet holders of their own purity.

THE ARAB

SUN SCORCHING THE DESERT, WITHERING bushes and spears of grass. Sun beating down on the camel train, parching the lips of riders, slowing thoughts, slowing camel feet, slowing all living things of the desert except—except the small, delicate mares capering alongside the caravan.

Silently the cavalcade moves beneath the fierceness of the sun until out of nowhere a cry tears the desert stillness. Sand clouds whirl and hulk along the horizon. An enemy tribe! As one, the riders leap from their camels onto the backs of the mares and gallop toward the enemy, white robes billowing, lances gleaming in the sun.

Now steel meets steel and the mares are no longer playful. They are whirling dervishes—spinning on their hocks, charging, rushing ahead, missing a flying lance, wheeling, stopping, starting, galloping until lungs are fit to burst.

This is tribal warfare. This is Arabia from the ancient days until the time when the deadly lance almost wiped out the fiery little steed.

Always the desert warrior preferred to ride a mare to battle. Banat er Rih he called her, which in Arabic means “Daughter of the Wind.” And that is how she traveled—a quick gust when the enemy pursued, a steady pace when no one threatened. Endless miles today and tomorrow and the day after tomorrow. And all of this she could endure on the scantiest fare, on dry herbage and bruised dates, and even dead locusts when there were no grasses.

But no matter how meager the fare, her master saw that her thirst was quenched. On the march he carried an animal hide to make into a water vessel especially for her, and at night he milked his camel and gave the fresh, foaming milk to the mare before he fed his family. She was one of his own tentfolk, eating what they ate, dozing when they dozed. Children sometimes slept between her feet, their heads pillowed on her belly.

It is doubtful if the desert men loved their horses as pets. Rather, they depended on them to warn, with loud neighings, of the enemy’s approach, to carry them swiftly and safely in battle. And so a good mare was almost never for sale. She was better than gold or silver in the purse. She was wealth, freedom, and power. She was life itself. To sell her was unworthy; to give her away, a princely act.

An Arab chieftain jealously guarded his mare’s reputation for swiftness. And he bred her to only the noblest of stallions so that the pedigree of the foal became sacred. Often it was inscribed on parchment and tied in a little bag around the foal’s neck, with a few azure beads to keep away evil spirits.

When a foal was several months old, it was given a camel as nurse-mare. The big clumsy creature adopted the nimble little one wholeheartedly, screaming in worried tones if it strayed, snorting softly when it came near. She refused to move from camp unless the foal accompanied her.

It was common practice to take these foals along on the march, letting them frisk beside their sedate stepmammas. Sometimes during the monotonous journey a young Bedouin boy would spring lightly onto a colt’s back, clinging stoutly with naked legs. As simply as that, first training began. Later, as a three-year-old, the colt would be taught the movements of galloping in figure eights, changing leads at every turn, halting in mid-career, and all this was accomplished without punishment of any kind. Horsemen of the desert were patient. They had Time.

To judge the qualities of an Arab horse, the desert men would study the head first. Were the eyes like those of the antelope, set low and wide apart? Enormous and dark in repose? Fiery as sun and stars in excitement? And the ears—did they prick and point inward as if each point were a magnet for the other? And was the face wedge-shaped? Wide at the forehead, tapering to a muzzle so fine the creature might lip water from a tea cup? And did the profile hollow out between forehead and muzzle like the surface of a saucer? If all the answers were yes, the animal was of royal blood.

Color was of no great concern. Chestnut or bay, nutmeg brown or iron gray, all were good. But, under the hair, the skin had to be jet black for protection against the rays of the sun. This underlying blackness is still found in Arabians today and it gives to the bodycoat a lively luster.

As for size, even the smallest Arabians are big enough. Warriors of all eras rode them to battle. George Washington’s Arabian charger, Magnolia, was delicately made, but she was big enough to carry him through his fiercest campaigns. And Napoleon’s desert stallion, Marengo, bore him on his long retreat from Moscow.

What were the beginnings of these little warriors? Where did they come from? Did the Creator actually take a handful of south wind and say, “I create thee, O Arabian; I give thee flight without wings”?

Storytellers of Arabia explain it this way. “Since time’s beginning,” they say, “the root or spring of the horse was in the land of the Arab. Our sheiks found them running wild. They caught the foals and gentled them.” History can discover no better answer. The Arab horse is the oldest domesticated species in the world. Early rock drawings depict slender horses with arched necks and the typical high-flung tails, for all the world like today’s Arabs.

The storytellers relate that the Prophet Mohammed would tolerate only the most obedient mares for his campaigns. To test them he penned a hundred thirst-maddened horses within sight and smell of a clear stream. Turned loose at last, they stampeded for water but, almost there, they heard the notes of the war bugle. Only five mares halted. These were chosen by the Prophet to mother the race.

One of the five was named “Of-the-Cloak” because of a curious incident. A rider, escaping from an enemy, threw off his cloak for greater freedom. Picture his surprise when he arrived in camp to find that the arched tail of his mare had caught and held the cloak. Ever afterward this mare’s descendants were called Abeyan or “Of-the-Cloak.” Today the up-flung tail of the Arab is one of the chief characteristics of the species.

When recent wars threatened the Arabian horse with extinction, Sir Wilfred Blunt and his wife, Lady Anne, imported the finest Arab mares and stallions into England. They knew that Arab blood is a white flame in its purity and, if it were snuffed out, there would be no way to refresh the blood of modern breeds. Today America is helping in the crusade which the Blunts began. There are now more Arabian horses in the United States than in all Arabia! They are used for pleasure and for work on ranches. But these uses are of small importance. Wise horsemen are carrying on the strain, breeding Arabian stallions to Arabian mares to preserve the blood in its purity. Then it will always be available for future generations. Arabian blood is like the rare elements added to steel which give it the superior qualities of fineness and strength.

And so the blood of the “Daughters of the Wind” has streamed west, its strength undiluted, its character unchanged. In the wide-set eyes of these Arabian horses there is still the fire of sun and stars, and in their motion the flow of small winds and the tide of great ones. War horses. Builders of other breeds. Yet holders of their own purity.

About The Illustrator

Wesley Dennis was best known for his illustrations in collaboration with author Marguerite Henry. They published sixteen books together.

Product Details

- Publisher: Aladdin (November 17, 2015)

- Length: 208 pages

- ISBN13: 9781481442589

- Ages: 8 - 12

Browse Related Books

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): Album of Horses Hardcover 9781481442589