Plus, receive recommendations and exclusive offers on all of your favorite books and authors from Simon & Schuster.

Table of Contents

About The Book

• Reveals how mask rituals are akin to shamanic journeying and allow the mask wearer to personify an ancestral presence, spirit, deity, or power

• Examines animal guising and shows how mask customs are tied to creation myths and the ancestral founders of a people, tribe, city, or nation

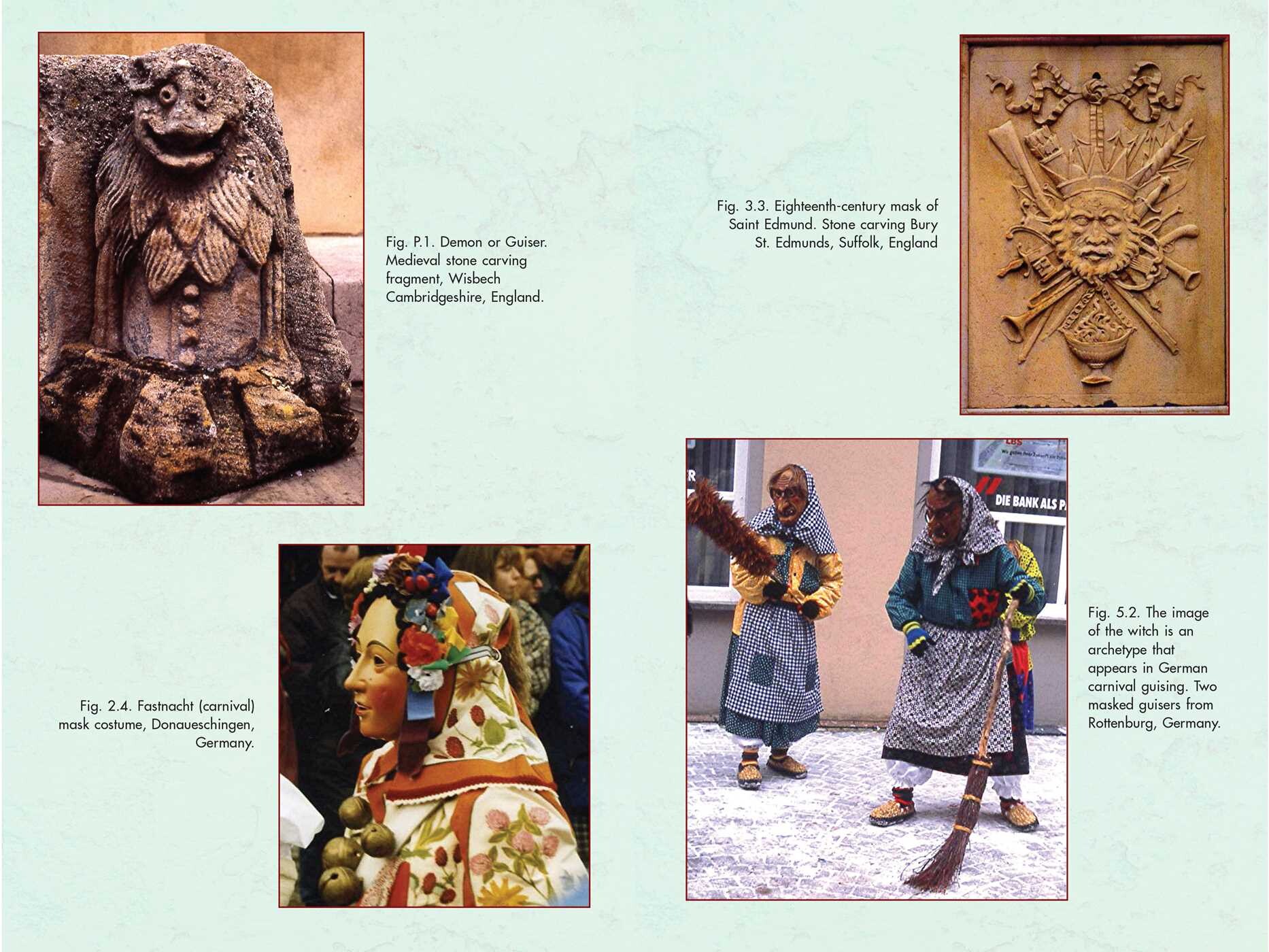

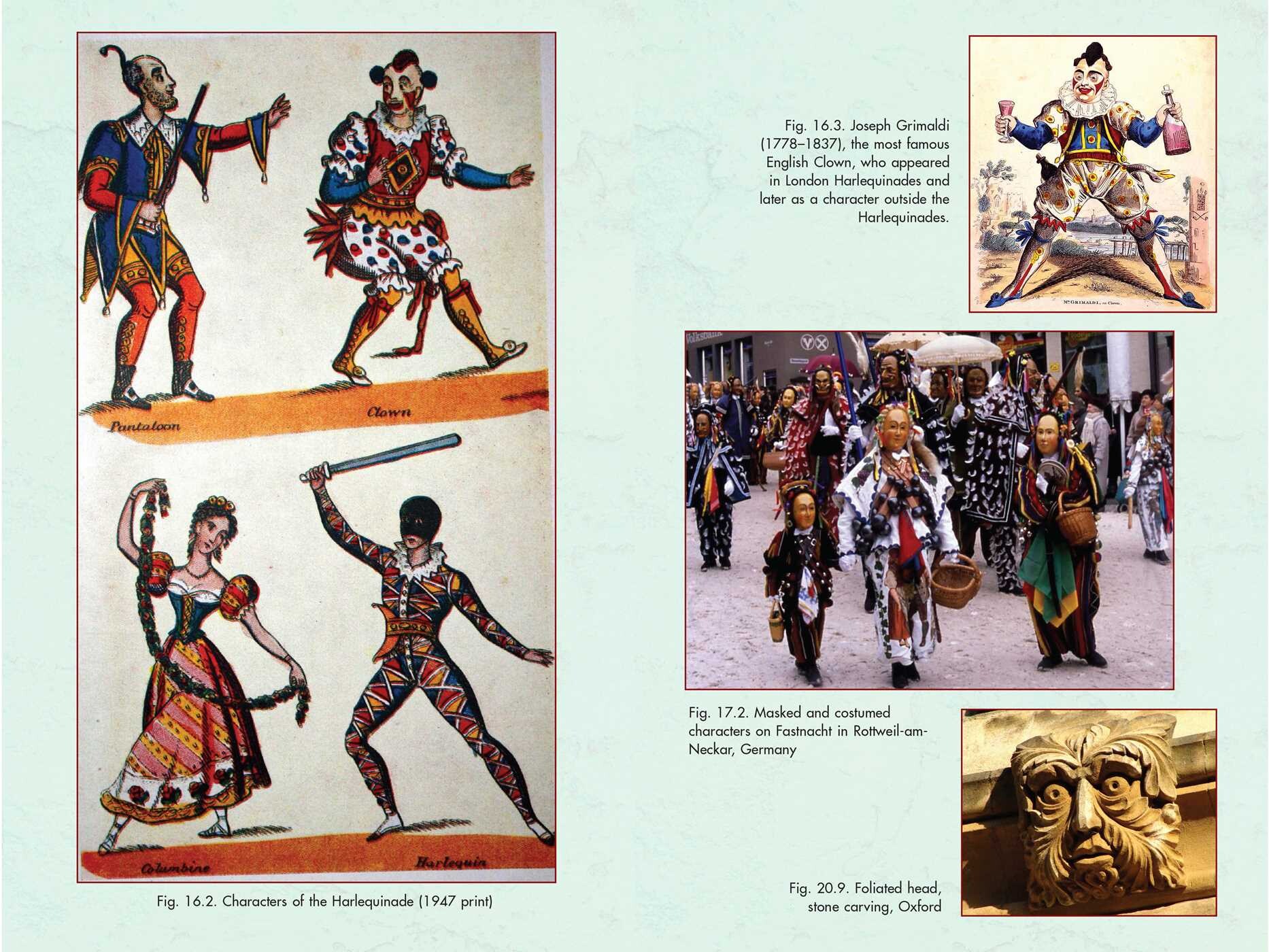

• Looks at morris dancers and mummers in the UK, Krampuslauf and Perchtenlauf in Germanic areas, the Gorgon myths of Greece, Norse Berserker rituals, and the annual Black Forest rite to awaken ensouled masks every spring

There is a spiritual power in masks that transports one into realms unseen and gives voice to things unspoken. Within the context of ritual, putting on a mask places the wearer at the intersection between the present and the past, the living and the dead, this world and the Otherworld. Masks make it possible to activate ancient archetypes, with the mask wearer reanimating or personifying an ancestral presence or spirit, a deity or power, an animal or a being of the eldritch world.

In this illustrated study, Nigel Pennick explores the magical and spiritual aspects of mask wearing from ancient times to the present. He examines the many mask traditions around Europe and shows how mask rituals are similar to shamanic journeying and near-death experiences and can induce ecstatic states that allow the power signified by the mask to take possession of the individual wearing it. He also looks at the practice of dressing up as sacred animals and mask wearing as it relates to ostenta, events that occur suddenly and without warning that are considered a token or sign from the Otherworld.

Unveiling the sacred power of masks, the author shows how masks allow us to transport into realms unseen, embody ancestors and otherworldly entities, and connect with traditions that stretch back to time immemorial.

Excerpt

Incarnating the Spirit Depicted by the Mask

There is a spiritual power in masks, hints of other things that remain unspoken, stylized yet ideal images of ideal qualities, otherworldly substances, ritually activated. For the mask’s wearer is representing the archetype, whether it be the ancestral or the dead, a divinity or a power, a being of the eldritch world or a character in a formalized play. The boundary line between human guisers, lifeless effigies, ensouled images of deities, and uncanny beings is always fluid and uncertain. The masker is located at the intersection point between the present and the past, the personal and the collective, the living and the dead, this world and the Otherworld--for the mask enacts the dialogue between the container and the contained, the exterior and the interior, the seen and the unseen. The mimesis of masked mumming means that the masker personates the mask’s character for the duration of the masquerade. The person inside is subordinated to the power signified by the mask. Whatever the being so personated, the performance takes place in the here and now and is operative by its present effects. For these are the masks of anonymity, worn by nameless guisers enacting ritual roles, incarnating the spirit depicted by the mask. In so doing, they partake of something of the eternal, the archetypal, that is present in the transience of keeping up the day. This book does not intend to be a comprehensive listing of every masked and disguised performance that has ever been documented over the centuries in Europe. It is not a literalistic catalogue of “here they did this” and “here they did that,” a work of numerical taxonomy, full of percentages and distribution maps that, however interesting, are artifacts of fragmentary historical documentation that often demonstrate little but drive the spirit away from an existence that is preeminently capable of infinite and joyful variation.

Tradition constructs the present out of the past, recognizing and celebrating those themes that have empowered the customs and practices of bygone days. History is not the past, and the future is not inevitable, only conditioned by what has gone before. History is a story that people tell about events of the past, and the future has no existence except in the imagination. History appropriates particular things that remain from the past and constructs a narrative from them. It is only of value if it resonates with and is useful to somebody now. Inevitably selective, tellers of history speak of things that are useful to their particular theme. They help to explain the present by recalling past happenings that preceded the present condition of things, events that explain, justify, and reinforce the present and indicate its potential.

Our experience of place is fundamental to our sense of being. Traditional society in each locality has a particular local way of looking at the world that is not reproducible or transferable. History is site specific; placeless events are impossible. In traditional societies, place names are all descriptive. Features in the land such as the shape of mountains and hills, bends in rivers, ravines, isolated rocks, fertile meadows, types of trees and animals, and the abodes of eldritch beings all appear as elements in traditional place names. Older languages have words that express the subtle gradations of slope, water flow, the shape of hills, the color of rocks, places where deer graze, the local names of plants and where they grow, places where snow remains longest after the winter, and the locus terribilis where humans ought not to trespass. The individual’s being in his or her “home ground” is grounded in the local culture as the repository of local knowledge. Place, language, and everyday life are enmeshed in landwisdom, a spiritual linkage that must be nurtured or lost. To recognize this is to acknowledge the genius loci, the spirit of the place. This is spirit in either sense of the world, both physical and intangible, emergent from the dark world of the indeterminate.

Ancient sacred places always had their human guardians, usually a hereditary role. The divinely enthused derilans who kept the holy wells of Scotland and the harrowwardens who dwelt in tumbledown cottages among the stones of power ministered to any passing pilgrim seeking an oracle or healing. These unpaid keepers assured that the hallowed wood, well, or stone would not be profaned, misused, or destroyed. There are those today who, unobserved, tend these ancient places of the land, where they still exist. They may not be hereditary guardians in the traditional sense, but they, too, are true dewars, spiritual gardeners who commune with the eldritch world. Theirs is the sacred stewardship of their spiritual forebears, bearing authentic testimony to their history, assuring the continuance of positive traditional values.

All places are meaningful, but places where something human happened--or is believed to have happened--are uniquely specific. They are landmarks associated with particular stories, with mythological and historical events. Whatever the event and whoever the personage, the place is made notable and special by the interweaving of topography, history, religion, myth, and institutions that carry on and commemorate the event in observances, rituals, and performances. But without institutions to carry them on, customs and traditions must die. Institutions in the form of gilds, whether officially sanctioned, unofficial, or even prohibited, have carried on traditional observances and guarded both intangible traditions and physical artifacts. From the religious gilds of ancient Greece and Rome to the craft gilds and rural fraternities of later times, the keeping places of sacred objects, masks, costumes, dragons, hobby horses, and giants have been maintained, often in secret.

1

Ensouled Artifacts and Death Masks

The Spiritual Arts and Crafts

In contrast with the materialistic worldview that is the commonplace, there is another sort of relationship that exists between people, places, and artifacts. When we engage physically in the spiritual current, then we develop another kind of consciousness of our place within existence. An artifact made by hand according to true principles gains an inner consistency, for the act of making is a spiritual path in its own right. For example, carving a religious image or a mask according to true principles produces an ensouled artifact. The materials used come from specific places and are chosen because of their innate qualities. They are not the products of anonymous factories, made by machines in vast repeatable quantities. The spiritual arts and crafts seek to realize spiritual ideals materially through a process that itself is the craftsperson’s spiritual journey. The initiation of the newcomer into a gild sets him or her on a path toward the hard-won mastery of the craft.

Ensouled artifacts emerge from the principles of traditional craftsmanship, in which, as the medieval German mystic Meister Eckhart taught, “working and becoming are the same.” Traditional spirituality is not just an inward thing: it also must manifest materially. “Those who lead the contemplative life and do no outward works are most mistaken, and on the wrong tack,” said Eckhart, for “no person can in this life reach the point where he is excused from outward works.” It is a spirituality independent of religious denominations--the world of the worker, the artisan whose function is to deal with physical reality firsthand. The realities of doing necessitate a practical approach in which the unquestionable presence of the materials always overrides abstract human theories and dogmas. This is not the dialectical materialism preached by modernity: the vision is that of the poet, the artist, the visionary, not of the professional cleric, the accountant, or the politician.

Death and Funerary Masks

The death mask is an ensouled artifact. It is a means of preserving the exact appearance of a dead person’s face, an image taken directly after the last breath has flown. Death masks are made by molding and casting. A flexible material such as plaster is put on the face of the deceased and allowed to dry. Then it is removed, and the mold of the face is now the matrix, a void in the form of the face into which material is put to make a copy of the original matrix, the solid form of the face. The mold is then broken, and the material object released. The solid of the matrix becomes void in the mold, then solid again when the material fills it. The death mask makes manifest materially the mysterious interconnection between presence and absence, here and not here, positive and negative. Depressions in the mold become raised areas, and the raised areas of the mold become depressions. What was hollow is now solid, and what was solid is now hollow. The death mask and the image made from it link it with the crafts of pottery and metal casting.

Frank Byron Jevons wrote that in ancient Rome, “One mask was buried with the deceased whilst another was carefully preserved, and the masks or imagines . . . were worn on the occasion of a funeral of a member of the household by persons who in the funeral procession represented the deceased ancestors whose imagines they wore” (italics in original) (Jevons 1916, 179). Funerary masks, with an image of the deceased person’s face, are well known from ancient Egypt, where they were part of the mummy case. Many Egyptian ones were made from cartonnage, a forerunner of papier mâché using linen strips with a binding material, which was then painted. Metal funerary masks were also used, the most famous of which is the solid gold mask of Tutankhamen. In 1876, a splendid gold funerary mask was discovered by archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann at Mycenae, Greece. He called it “the mask of Agamemnon,” though he had no evidence that it was. Several comparable Thracian gold funerary masks have been discovered in Bulgaria; the Sventitsata mound at Kran in the Stara Zagora region contained the remains of a body dismembered according to Orphic custom. It was identified as the mask of the Odrysian king Teres, who reigned from 460 to 445 BCE. Etruscan funerary masks were made in sheet bronze and attached to urns containing the ashes of the dead. The Romans made death masks that they used as molds to make the imagines majorum, masks that were deposited in the family lararium, the family shrine of the ancestors. They were worn at funerals, where they literally represented the dead.

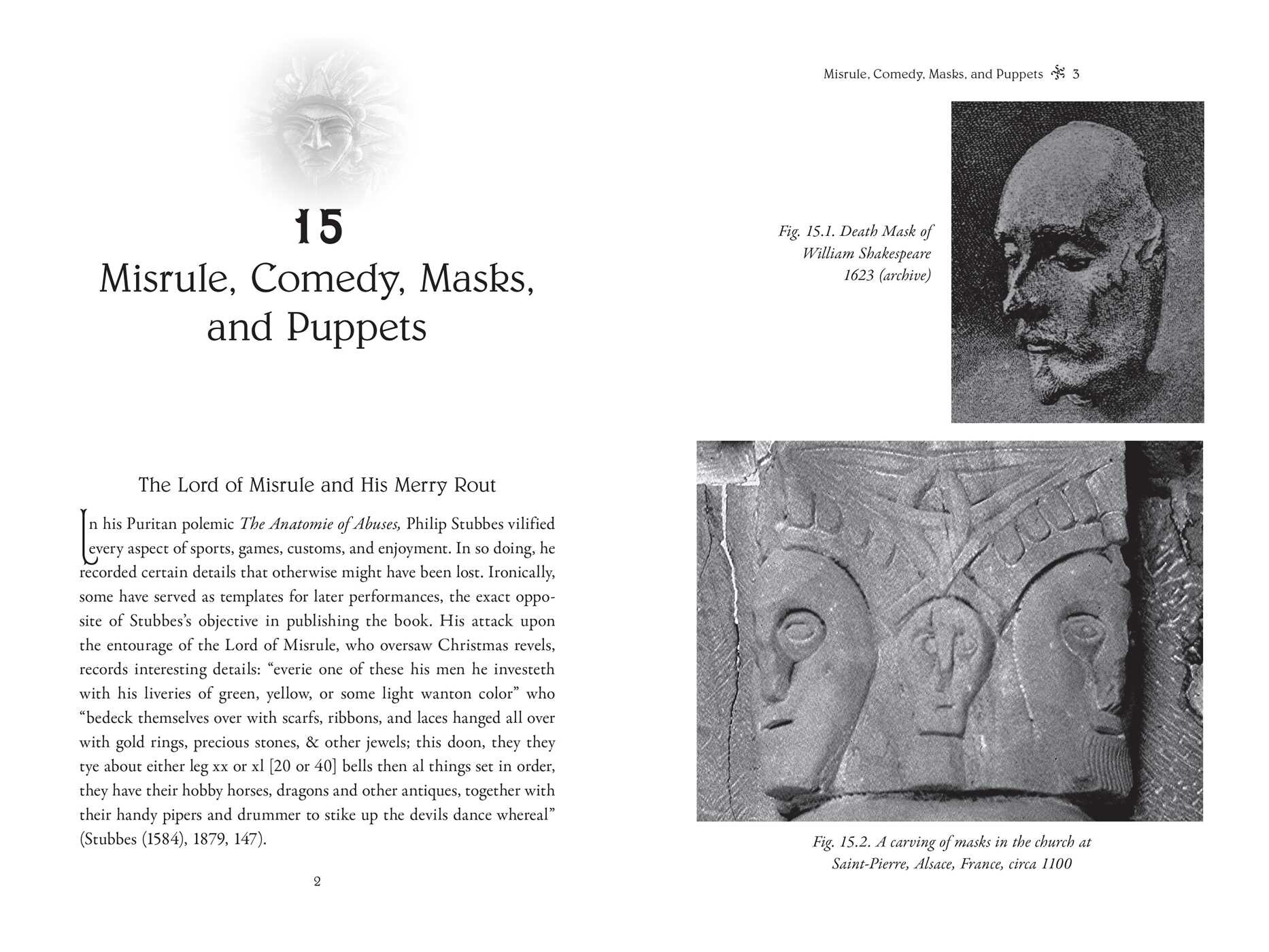

In medieval Europe, effigies with lifelike masks, cast from death masks in the Roman manner, appeared at state funerals of magnates and royalty. “State funeral of the fourteenth and subsequent centuries,” Reginald Cocks wrote disapprovingly in Britain in 1902, “were robbed of much solemnity in this country by carrying in the procession a life-like effigy of the deceased” (Cocks 1902, 431). In the medieval period, the effigies had lifelike painted and carved wooden faces, but by the seventeenth century, they were lifelike waxworks. The faces were cast from death masks. Westminster Abbey contained the effigies of several seventeenth- and eighteenth-century British monarchs: King Charles II, William III and Mary II, and Queen Anne. The last effigy carried in a procession was that of Edmund Sheffield, the last Duke of Buckinghamshire, who died in 1735 at age nineteen (Cocks 1902, 433). It remained customary until quite recently to make a death mask of a famous person who had just died. The death mask of William Shakespeare is illustrated in figure 1.1.

Fig.1.1. Death mask of William Shakespeare (archive)

Marks around the eyes have been claimed by medical experts to indicate the disease reputed to have killed a person. The death mask of the visionary poet William Blake still exists, and that of the Soviet dictator Josef Stalin, who died in 1953, is preserved in the Stalin Museum at Gori in Georgia.

Product Details

- Publisher: Destiny Books (June 7, 2022)

- Length: 336 pages

- ISBN13: 9781644114049

Browse Related Books

Raves and Reviews

“A thorough and sensitive review of the varied use of masks through time. Most valuable to me is Pennick’s understanding as to how masks allow us to outwardly reflect our inner spiritual reality. There is too little literature on this subject, and this book is a valuable addition, written with sensitivity and understanding.”

– Peter Coyote, actor, Zen Buddhist priest, mask teacher, and author of The Lone Ranger and Tonto Meet

“This book is a gem! As always, Nigel Pennick explores his intriguing subject with ferocious intensity, beautifully balancing his lenses from telescopic to macroscopic. He writes with a density of detail and archival attention, galloping through centuries in single sentences, crisscrossing countries and even continents in single bounds. His prodigious knowledge, gathered and retained over a lifetime, pours forth--a cornucopia of richness--and sometimes may seem like simple lists but which transcend as categorical abundance of evidence that lead up to his anecdotal expansions. Well done, Mr. Pennick!”

– Linda Kelsey-Jones, president of San Marcos Area Arts Council and director/curator of The Walkers&rs

Resources and Downloads

High Resolution Images

- Book Cover Image (jpg): The Spiritual Power of Masks Trade Paperback 9781644114049